I've known William Orbit for nearly thirty years. I first met him when I worked for Guerilla Records, a label he co-owned with Dick O'Dell. Dick had run Y Records previously (killer post punk label and far more) and was William's manager. William was busy working in the studio so rarely (if ever) came to the office but he always wanted every release sent to him and to know what was going on. As I remember he was always into those records that had that perfect balance of club and melody.

When Guerilla went under (for various reasons) I ended up initially record shopping for William (basically heading to Soho with a pocketful of cash and returning excited about all the new music I'd bought) which then turned into working in the studio and helping on the batch of Warner Bros releases William was working on which included Strange Cargo, Caroline Lavelle and a new Torch Song album. This conversation starts where we left off with William revisiting Torch Song...

William Orbit: Are we good? Can you hear me?

TP: Yeah. How you doing?

William Orbit: Fine's been a while mate. (laughs)

TP: I know, I know. How's things?

William Orbit: Exciting. Yeah. Yeah. I mean, you know… Things are moving… I've just been mastering four records because I'm putting out three re-releases right now. And then the exciting thing for me is my own actual record.

TP: So what are you re-releasing?

William Orbit: I’m starting with a Torch Song record and then the two subsequent albums. One a month starting in February.

TP: Is this just a digital thing? Are you doing records as well?

William Orbit: Um, Paul… There's a story. Six months waiting time for vinyl. I mean, when we were working together, you just went down and mastered it and got your pressing back a week later.

TP: Yeah. Well four weeks I guess back in then…

William Orbit: Now it's six months.

TP: Well, I have found some quicker routes… I’ll come back to you at the end. Quicker lead times and a little bit more expensive, but they can deliver.

William Orbit: Do it. I'd love to speak with them. Yeah. Because I was just literally yesterday at Abbey Road and I was mastering for vinyl. But I can't really talk about it because it's an album that's not due for release until the summer so I would love a back door into a pressing plant that could do a turnaround. I'd love that because everybody loves vinyl.

TP: Yeah. I mean, it's funny, isn't it… I ordered a record by Nala Sinephro, this sort of harpist that makes modular music via Bleep, which is like Warp’s online store. I think I bought it in September and I've got a notification this morning that it shipped <laughs> and you're like ‘wow’. I mean this is no diss to Bleep as they are brilliant it’s just an indication of the state of pressing records right now.

William Orbit: What happened to all the plants? They just must have got scrapped.

TP: I don't know. Yeah. Vinyl factory still have theirs… The old EMI Plant.

William Orbit: Um, I mean, lathes are expensive pieces of equipment. Very complex. A lot of maintenance. Yeah. But it, I mean, valves, you know, there was a time when everybody went to transistors, it was the new thing. And people didn't realise that actually valves, you know, tubes sound better. So all the valve factories shut down except one in China. So when everything picked up and everybody wanted valves again and that factory was booming, servicing the entire world until everybody else realised. We shouldn't just shut down this stuff. I mean, Paul vinyl wasn't a thing ten years ago. Uh, downloading was a, was a thing. Now nobody downloads anymore. They stream and they want vinyl in their living room.

TP: You know there's some ridiculous statistic about the amount of people that just buy records to put on the wall. (laughs). But you know, I mean obviously the world we are in is a, you know, an awful lot of people that still love buying records and playing them but it is a funny time when it comes to all that…

[An ICM poll from 2016 says 48% of people who bought vinyl last month have yet to play the record. Some 7% of those surveyed said they didn't even own a turntable, while a further 41% said they have one but don't use it.]

William Orbit: It was lovely mastering. I mean, it's great. And I've got Jeff Pesche at Abbey Road and I, I tell you my album, you know, my material, you get a bit familiar with it. You've been working on it for a long time. It's immersive. Then suddenly it's finished and you can't listen to it for a while. Then when you get a great mastering engineer doing his thing, whatever it is he does, it’s as if it's a brand new item and it’s very inspiring.

TP: Jeff Pesche – he’s been mastering for years….

William Orbit: I mean, he started as a bike messenger and he was taking tapes into a studio and he said, ‘what is it you guys do here?’ And they explained and he sat in and eventually came an intern and eventually became the man. Then he was at Townhouse and now we’ve been working together for three decades. So I don't have to say a lot. I don't have to communicate much with him. He knows what to do.

TP: Oh, you can't beat that experience. You grew up in a time when it was slightly different that there was lots more separation… You had desks, you had 2” tape… Do you think you still hear with those ears or have your ears become very attuned to this Pro Tools, soft synth, plug-in era we now live in.

William Orbit: Good question. I mean, I've got a lot of sessions which have just been digitised off the tape at 24 bit with nice high end and I'll really hear it. That's why old records sound better. People would still ask ‘William is vinyl better?’ and now they don't ask me anymore because they know, and they are prepared to spend money on vinyl. When you've had something that has never been digitised… You know recorded via analog tape valves, more analog tape and then onto plastic, you can hear it.

There was a point with tape and recording in the 80s that it retained all the things that we didn't like such as the artefacts and wow and flutter and all the bleed through and all those things which you now realise sound marvellous. Like now when I'm listening to something that's on tape and I can hear the ghosting of the track that was recorded on the adjacent channel, something you tried to avoid, it just sounds fantastic. Like this extra mystery.

TP: We call that atmosphere. I think you're totally right. I mean, when I was making music in the early 2000s, the first thing we would do was record a bit of dead air off a record…

William Orbit: Yes and then you have someone like Burial who will take this to extremes. It's just like the crackle is, is as loud as any, as the drums. And it's, it's beautiful. I love Burial.

TP: You like that?

William Orbit: Yeah. I love it.

TP: Have you heard the new Burial?

William Orbit: No. Let me make a note. I did a mix for Radio One the other day and used one of his tracks and a lot of people commented asked me, what was the, what is this fantastic piece of music? It's fantastic. The samples are done so cleverly. Yeah. It's terrific.

TP: Well, you like atmosphere, you know, I'd say that, that is always a current theme in your music, so I can see why you find joy in Burial.

William Orbit: Well the ear will discern those things that are on a sort of separate level, you know, the ghosting and the subtle. Like the drums… When you have ghost notes. And you've got your little bits and your little taps and stuff, which are very quiet, but they often, they often determine the funkiness of the groove. And it's the same with the audio across the spectrum. I mean clean music can be great, especially in dance music, saying that…

TP: Yeah. I think if you listen to like Clyde Stubblefield or, you know, like James Brown drummers that are killing those “funky” beats or whatever, you can just hear those ghost notes. It's those subtle sounds that make it, cause you know, it's like you sit in a studio and if everything is obvious and everything's loud, it's like, this is really boring.

William Orbit: I listen very quietly when I do a lot of work. In the last 18 months I've been solely on headphones. I've done three records now on headphones. In fact, they just packed in yesterday. I've used the same pair of Senheiser cans, very consistent, for years. I was in a studio the other day working on a track with an artist and its like a guilty pleasure. We all loved it, being in a studio after covid.

TP: You kept a physical studio for years, probably until you went to LA to work on Madonna…

William Orbit: I had one in Los Angeles as well.

TP: And now you’ve literally got a MacBook… It’s funny isn’t it. Is that it? And a soundcard and keyboard?

William Orbit: Sort of.… I mean an awful amount of material is being recorded through great big racks, full of gear, you know, especially when I’m on the production side so it's not all virtual synths. There’s masses of stuff that's real. Now and then I patch out to a synth. I still love the MS20, the Juno…

TP: So you've kept some gear.

William Orbit: Yeah. Yeah. But it's all leaning up in against the wall getting dusty. It’s not a full studio like I used to have.

TP: Anyway, look, answer some questions for me. I was unaware that you were born in Shoreditch. Had your family always been in that area?

William Orbit: Well, that’s not actually correct. I was born in Bow. Well my father was from Sheffield, but my mum… Her dad was Italian and in the war, they were moved into the docks and they became east enders. I was then born in Bow. My mum was a teacher. She was like a young student teacher doing infants. She was basically straight out of Call The Midwife. She became a head and worked in all these schools in the east end but to be honest most of my life was in north London. I did once have a flat in Shoreditch and I remember my mum coming to visit and she said, ‘this area still reminds me of how awful it was back when I was student teacher with The Crays (notorious London drug gang - Ed) and the violence, the gangs.’ It's romanticised but they were tough people. Now it’s all Shoreditch House and boutiques.

TP: So you are an actual, proper east ender born where you can hear the Bow Bells…

William Orbit: I'm a proper east ender. My dad wanted to be a school teacher too. He taught English and to teach, to be in the professions in those days, you had to speak kind of “Radio Four” (basically an upper class tone - Ed). And so he sort of taught himself to speak radio four, really listened to the radio all the time. So when his friends would come from school for tea, he had to translate for his mother who spoke in a very broad Sheffield accent. So my parents both spoke nicely if you like. So I'm sort of torn because I speak like them but then there's also a bit of London there as well.

TP: I read that your mums name was Ferrari… It doesn't get more Italian than that does it. So tell me how you got the start in music…

William Orbit: I wasn't in anything remotely you'd call the music business until 1983… It was all I wanted to do was that, but I didn't know how to be in it. It wasn't like today and you couldn't get into studios or anything like that. So I had a band I played in playing jazz guitar at a pub. I did all sorts of work, all sorts of jobs. And I was very frustrated.

But I remember when I was a kid there was this visit to an uncle who had this little tape recorder… This is like the 60s you know… And I kind of like, co-opted it, it was mine. I'm having that. I took it and I remember driving back and it's like, ‘oh you can record sound’ and was the biggest moment in my life aged about 11. So since then I was obsessed with tape recorders and recording. Then my dad had this guitar.. He got it in the war. A little old guitar. He got in Yemen when he was there. Once again, you know, once it was in my hand, it's like, I'm having this. So those two things… That’s where it started but I didn't get into any kind of serious recording until ’83.

William Orbit: I remember being at school in school assembly and I'm about nine and they played the Dr. Who theme right over the speakers. And I was like, ‘how do you do that? How does it come from school? This is something you only hear on the TV set.’ And I went to a teacher and asked and this really patronising teacher said, ‘oh no, you don't need to know about that. It's all tech, it's some clever stuff.’ It's like, ‘no, I really wanna know’. So I was obsessed with the idea of sound before I was obsessed with music and chords.

And then I discovered JimiHendrix and I discovered Pink Floyd. It's like, ‘whoa, here we go.’

TP: And where did the electronic sort of side of things come from?

William Orbit: I never considered electronic music being part of it. Although I'd heard and loved Can. Right. You know, my headset coming from some foreign radio station. But when I was squatting in Notting Hill there was this band called Crazy Lizard. And the one of the members had a synth and she would just make noises through an echo box. And of course, once again, it's like, I'm having this… I didn't actually take the synth, but it's like ‘wow, you can actually buy a synthesiser and make noises.’

TP: Yes… (laughs)… Well then did you go off down Charing Cross Road to the music stores?

William Orbit: No, I did not. I just was working, working, working… But then I met the people who would become Torch Song. I mean we are talking around ’79 and they bought this thing… The Wasp. Do you remember?

TP: Yeah, yeah, yeah. The little yellow thing.

William Orbit: Yeah. And the keyboard was all like a plastic kind of there's no keys. Just this kind of printed out sort of strips that you pressed. And then I discovered the WEM Copicat. When I was 17 I was a roady for this band as I was too young to be in it. They modelled themselves on The Grateful Dead basically. But they had this synth player and she ran her synth through a WEM copicat. Right. So I had my guitar and I had a little, what do you call those microphones? Stick on a guitar transducer mic. And I run for the WEM copycat and it was like, ‘woaaah’. I've listened to John Martyn and I would just echo my guitar away. And so, you know, I, I fell in love with echo, and have been in love with it ever since though it wasn't until some years later that I was able to actually obtain these things.

TP: So how did you get your first studio together?

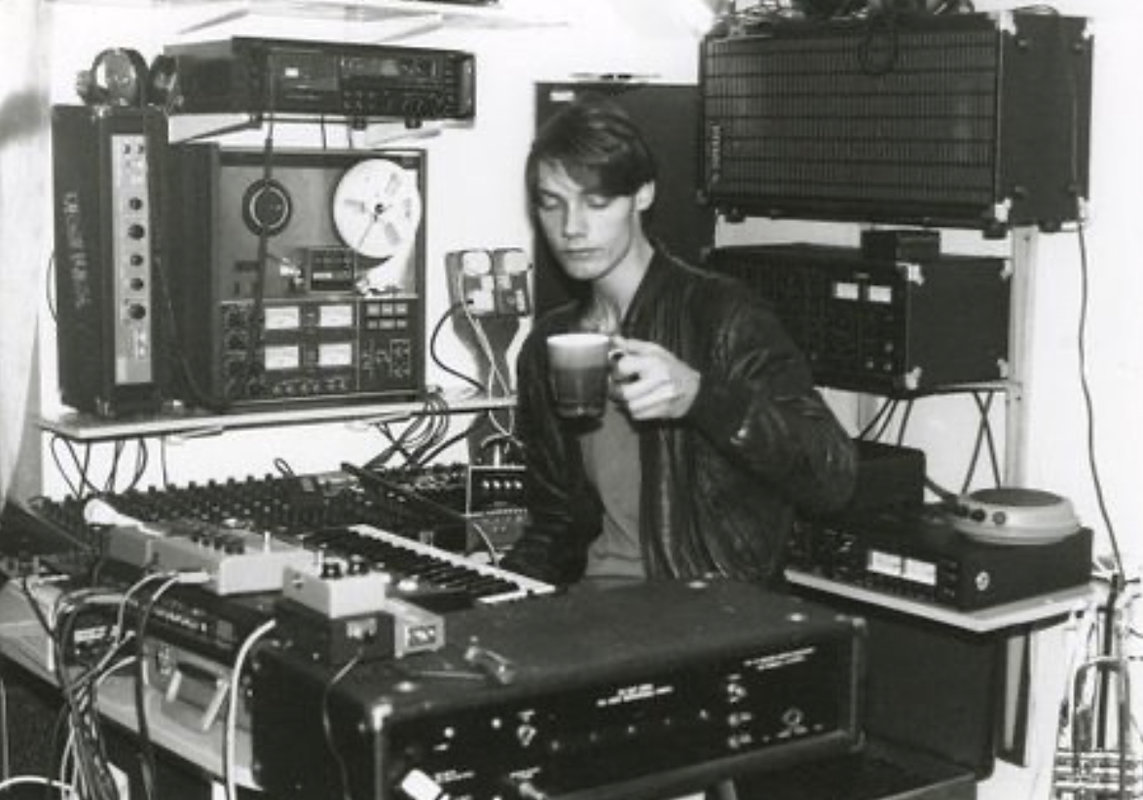

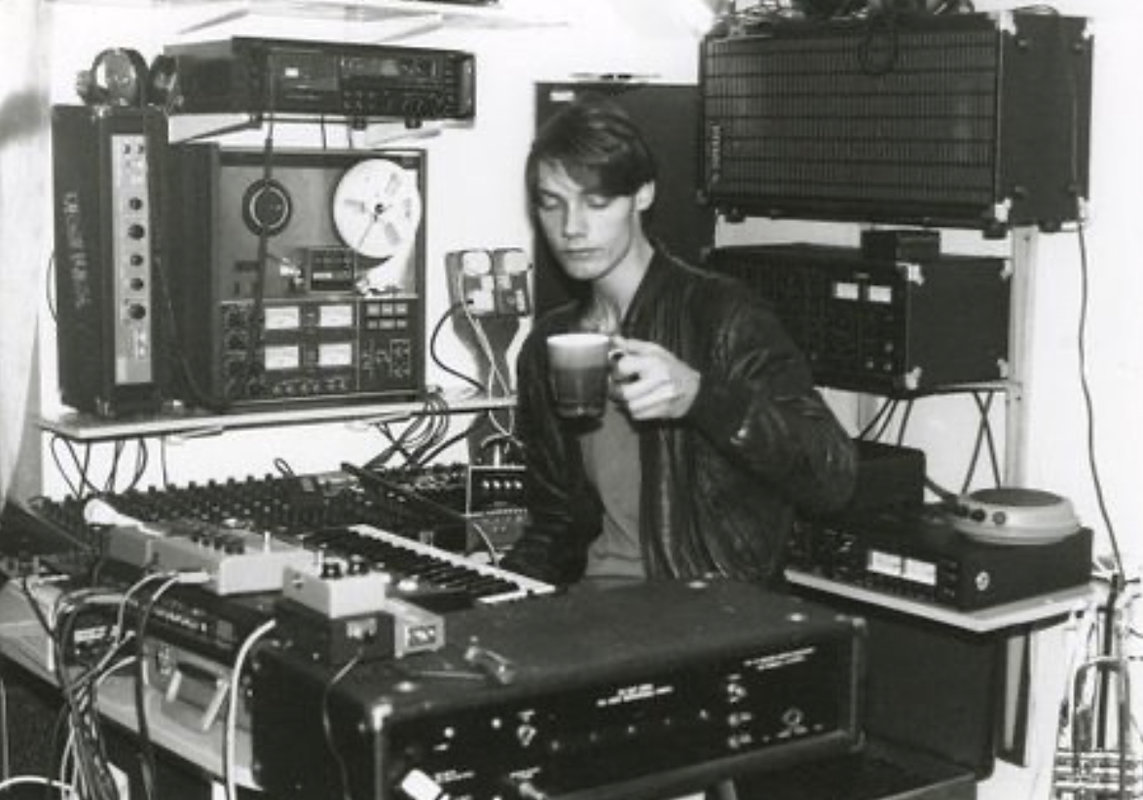

William Orbit: I was squatting in Paddington… There was a whole school that was a squat… And I was working in the oil business now actually making some money and living in a squat and the gases are always on, the water's running, the electricity. Nobody ever turned it off. So no expenses… And we were also selling clothes down Portobello Road that we’d find in jumble sales. And it's like, ‘well, we've got some money.’ And next door to the squat was this secondhand shop two doors up from the school. It was called Gus and Rays. And it was two Italian guys and they sold secondhand stuff. And half of it was musical instruments. I filled up the squat with all this stuff. And then Torch Song was born.

TP: So is the squat you talk about the Centro Iberico?

William Orbit: Yes. The school was this enormous Victorian structure but we lived in the caretaker's cottage on the playground as in those days those schools would always have a caretaker and they always lived on site. They'd have a cottage with their wife, you know, and their kids. I mean, it was a great place. Bands like Throbbing Gristle would play there. So it was a marvellous. And you know, there's like the metal workshops there with all the tools it's like, wow, what a place to live. So it was heaven.

TP: So, there was basically a performance space in it. There was a hall or something?

William Orbit: There was and that's where the bands would come and play.

TP: Was this early Throbbing Gristle or were they established by then?

William Orbit: I think they were reasonably established. Well… I certainly knew who they were before they came. It was a lot of punks came as well. Like it was the punk era. We weren't punks, you know…

TP: I think I saw a photo of your studio at this stage.

William Orbit: Was I drinking a cup of tea?

TP: Yeah. It's quite developed.

William Orbit: I mean, sadly, you know, nobody took photos much then, so there's like whole vast eras that aren’t documented, whereas of course everything's photoed now. We made a great effort with the studio to make it professional and it was marvellous. You know… We had a Roland Space Echo, MXR flanger and then I was just making music all day long. I gave up working in the oil company and just made music. So I'm just there all day long making music and experimenting and learning my stuff. Then we start sending out cassettes… We had various people in the band like Neville Brody (legendary graphic designer who founded the house style at The Face and went on to design sleeves for Cabaret Voltaire and more - Ed) . He was in the band for a while… But you’d make cassettes and send them to labels and they would always write back and go, ‘not sure, you know, keep it up, keep in touch’. You know, it was a real proper letter written by hand would keep 'em all in a great big stack. And then we had to move because the school was gonna be demolished and we moved to Little Venice. We got an eight track tape machine and we got even more serious and then got a call from Miles Copeland saying, ‘would you like a record deal with IRS?’ Bingo. That was it. We got a 24 track. We were on the road.

So we've now got a two inch tape machine and we've got this great record deal… We've got publishing deals and we are making records now. It was very exciting. Two inch recording on those big fat two inch tapes. I remember handling the very first one. That's it? You have the record in your hands on one of those and you are going and doing the mastering.

But it didn’t really work out you know… We just weren't selling records. And in the end I took over the studio and decided to rent it out as a commercial venture and that's how I got to learn all about records because you know, people are coming through and I'm doing remixes because at the time you could get paid for doing remixes. So I'm getting all these tapes coming in. It's lovely to open up a fresh tape put it on and just listen back to the raw multi track and in time I was learning… Learning about recording and producing and that morphed eventually into Bass-O-Matic after a couple of moves…

TP: I love that. So hold on. Before we get there, let's take a step back. So one of your very early pieces, which I really, really like was for the Young Blood film with Rob Lowe. ‘Opening Score’ and then it’s on Strange Cargo I under another name.

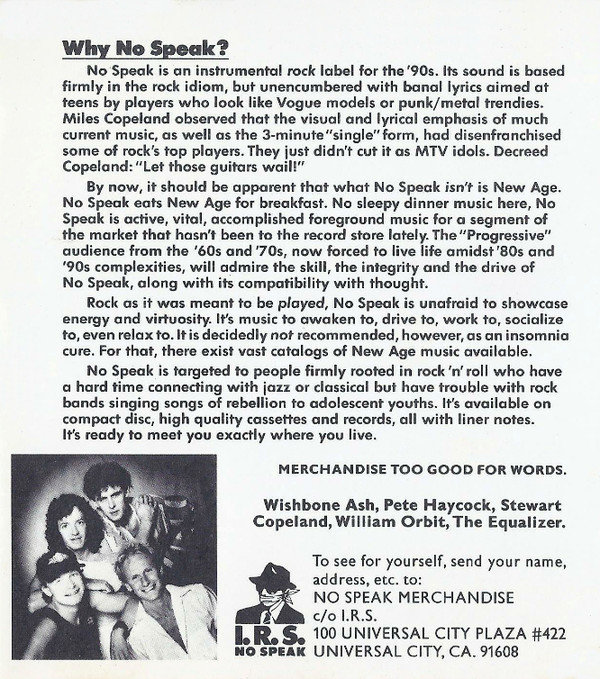

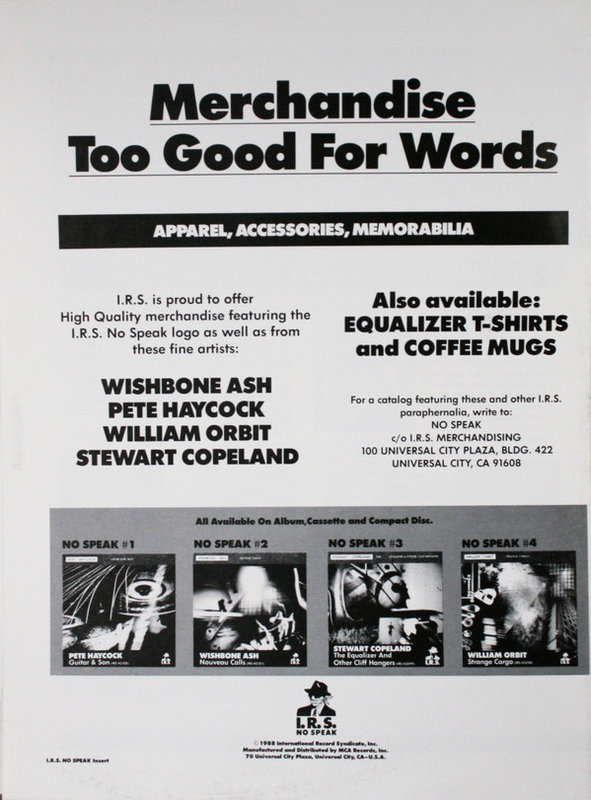

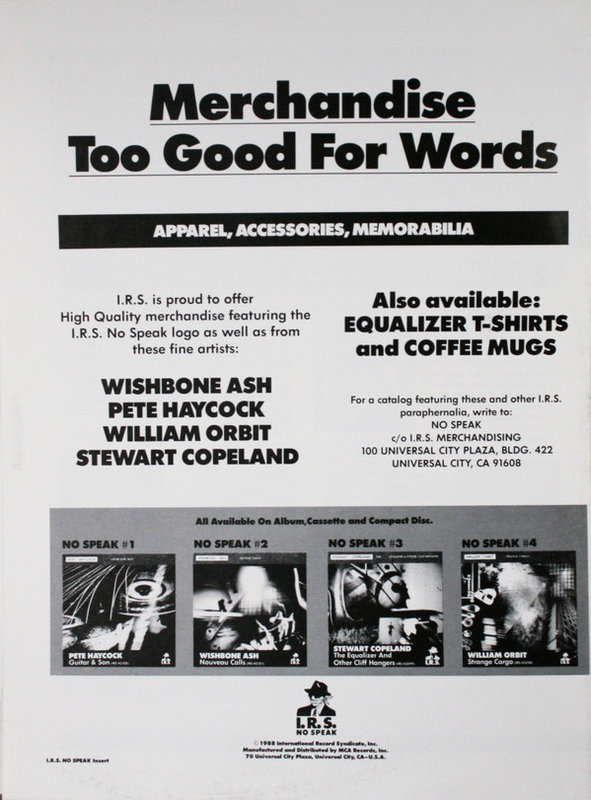

William Orbit: Well. That's right. Miles from IRS our label produced this film about ice hockey. It also has one of the earliest appearances of Keanu Reeves. And so I scored it. It’s the only time I scored a movie. I did all the cues. I learned. It's like, ‘oh, this is how it works’. You do a spotting session and you work out which piece of music you need to put with which particular scene. And there's like 40 little cues and we went to the mixing session in Los Angeles. And there it is… It's the film and it's out there. And then from there Miles said ‘why don't we do an instrumental series of records?’ and we call it No Speak…

TP: Got it…

William Orbit: Miles is a visionary. I can remember him taking me out to lunch one day and just ranting and raving about mineral water. There was no mineral water at that point and then mineral water became a thing. I can remember him designing this kind of jukebox sort of on a computer. And like 10 years later, it's like, that's Apple Music. So when he decided to do No Speak, the instrumental arm, it's like, ‘ah, I'm up for that’. And that's how that first Strange Cargo record happened. And of course we put on some of the music from the score. Yeah. And then that started me off in this whole process.

TP: You can sort of really hear your sound at that point. You can hear the atmospheres and textures that I’d say are pretty common in all your work… Would you agree?

William Orbit: I would. I mean that Strange Cargo record is the first record I've made where I actually think I got good. Some people are great when they start and they stay great but I think it took until then for me. When I started I think some of the things I did were a bit wonky until that Strange Cargo release where I found my feet and I think it was because I trusted that use of almost the atmospheric. And I would allow myself to become totally obsessed with sound… To the point where every bar, had to hold my attention and make me think I could listen to this forever and ever. It's an obsession. I mean, I'm just very happy in the world of sound. It's just colours to me.

TP: Well, it feels very intuitive. I was listening to ‘Prepare To Energise’, which still sounds immense. It sounds sonically incredible. And the thing that struck me by that one, funny enough was I, and maybe I just never heard it before. I never thought of it, but I was like, ‘wow, this is kind of very Yellow Magic Orchestra’ in a funny way.

William Orbit: We didn't listen to other music to be honest. I mean we listened to Cabaret Voltaire and people but I've never really been influenced. I've never gone. I gotta sound like so and so. It's not like I'm being heroic in saying that I just don’t want it to infuse what I do. If you've got this confidence in sound, it's like, well, I know it's right. And that’s all I need to know. So that track, well, what happened was we bought all these Roland sequencers. Like I forget the names of them, but they were very hard to program. The manuals were in Japanese, and it was all done by clock and step programming. I thought, well why can't I have them all running together so they're all communicating. We had this great engineer called Lincoln Fong and I asked him ‘can you make it, can you work it out?’, so he got this soldering iron out and these transistors, and he made a little box, which we called the Fong Box, obviously, which did precisely that.

So now it's like, ‘oh my God!'. I can now do tracks where everything lines up. It’s got this control pulse and everything's tight cause before midi everything got loose. I wasn't being a pioneer, but it was just my own little opening into making really tight electronic sounds. So we were like ‘well let's make a track’ and I started to, and that became ‘Prepared To Energise’. So, if you look at the first pressing, it's called ‘the Fong Test’. In the end he went off to work with the Cocteau Twins and lots of great people.

TP: The interesting thing I think with that record is the keyboard sound and the effects, and also what key it's in are definitely sounds I associate with you…

William Orbit: Everything has to conform. It's like an architect… No matter what the music comes out as, whatever form, it could be the most ambient piece of music ever, or something like completely nuts or whatever you must get the underlying melodies right. In every respect. I mean, I make a huge amount of effort in making kick drums in tune. And some of it is pure physics. It's just like if you've got two bass things and one of them isa semi-tone outta tune its just gonna thrust out of the mix. So everything has to conform. So melodically, it's got to be really, really tight. And when I have people do remixes for me, especially these days, I do say, ‘look, do whatever you like, but honour the chords.’

TP: I was thinking about that because when we worked together on, uh, the last Strange Cargo album ‘Hinterland’

William Orbit: Yeah. That's when I went to Warners.

TP: So that's when we were in the studio together and I remember we got a Kruder & Dorfmeister remix right. And I remember you very clearly saying, ‘they mustn't just remix it. They have to reinterpret it in their voice.’ And I was like mnnn…

William Orbit: But if you're going to mess with the chords, you must know what you're doing. We don't wanna have an ouch moment.

TP: Yeah. Well I think your point was they must kind of just put it through their tap or their filter or their… Do you know what I mean? They mustn't just loop up the beat and stuff…

William Orbit: Somebody mentioned that remix recently Paul. I can't remember who it was. It's a great remix. I got lucky with a few of those. We had some good people. The previous album we had Spooky and Underworld… Spooky, who, you know of course, were signed to Guerilla… And Underworld, I guess it was Dick O’Dell who set this up or the guys at Virgin know, I'm not really sure… But they did these marvellous mixes. They still hold up so well… It was a good time. I had a singer I liked in Beth and these great remixes…

TP: I ran into her not long ago.

William Orbit: Beth works incredibly hard.

TP: So lots of the titles of Strange Cargo tracks are cinematic in feel - well ‘Harry Flowers’ is a cinema reference… Was it cinematic music you had in mind when writing these tracks…

William Orbit: I mean, it’s always telling a story. There's a story. That's why I like things to happen all the way through the song. Something happens near the end. It's not like, oh I've run out ideas halfway through. I just repeat everything. But what you were saying about let's go back?

TP: Well, no, I was just asking where the names come from…

William Orbit: Actually naming tracks when they're instrumental is very hard. If it's a song with lyrics, well that's easy enough, you know… There's always material in a song for a title but with instrumental music it's really hard. Sometimes it's the hardest thing. With this project Laurie Mayer (Torch Song member) just said, why not Strange Cargo? And it's a film… It's a Clark Gable and Joan Crawford film. And it just felt right.

TP: A lot of your Strange Cargo titles are places… Is there a new Strange Cargo album in the works? Or will it be a William Orbit release?

William Orbit: It won't be called Strange Cargo, but it is a new William Orbit album though it’s absolutely in keeping with those albums.

TP: I remember being in the studio with you on the last Strange Cargo record and being amazed watching as you sort of played the mixing desk like an instrument… Pretty much just sort of playing the tape and playing the 24 tracks that are sitting behind you… Things going on and off, effects on and off. And it just being like, ‘wow, that is amazing'.

Wiliam Orbit: Gone. I don't think that I have that skillset anymore. The tape machine working, the fades chopping quickly. It's like, wow, you're not seeing this hand.

TP: I mean the interesting question or thought is that this way of working produces lots of mistakes and lots of mistakes equals lots of really interest thing happening in the music. You know, how do you feel about sort of automation and you know, and it's effect on sort of modern music. The fact you can draw in every effect perfectly…

Wiliam Orbit: I think you adapt because you want to… My term for it is curated serendipity. This randomness that you need to curate obviously, but is the golden gift. It's the gift from the gods, if you like, is the accident. Well… Obviously when you are playing in the studio you get writing failures that happen a lot with echos suddenly going out of control, but in a really cool way… It still happens with digital recording.

Then there’s the benefits. I mean it's very easy to match tracks. In the past it was very difficult. You had to sort of speed the tape up or use a pitch changer, which is very expensive technology. Now you just basically type the BPM and the key and you're like, boom, they're done. It's like DJing. Right. You know? Well you think, oh, that, that just takes all the fun out of it makes it too easy. But actually what it does is it actually opens up vast amounts of, um, creative, um, serendipitous possibilities. Its the same with Melodyne. I love that program because of what you can do, create as well as a fixing and remedial remedial tool for subtle invisible mending. It's an incredibly creative tool for harmonies pitch and time. You think ‘oh that takes all the fun out’, but actually it opens up broad landscapes.

TP: I tell you the other bit of advice or something I remember you saying… You'd be like, ‘can you stop looking at the screen’? The music doesn't come out of the screen…’

Wiliam Orbit: They say, once you see waveform, it's all over… Here's a weird paradox. I live for sound. And I'm very good at frequencies and decibels, but you play me something and it has a weird honk in it with the screen now I can see a visual representation. You need the meters.

TP: I think your point was you shouldn't be looking at rows and rows of the tracks that make the music, Close your eyes and listen to the whole…

Wiliam Orbit: Absolutely correct. When you are listening back to it at some point in order to gain a broad view of how you feel about it or if it’s completed yeah… That's the point you should absolutely do that. You should be listening to it as a piece of stereo music and nothing else to do with it going on. Because you will hear it differently. And of course listen to it from next door and put your headphones on back to front and different speakers, different this and that. But you're absolutely right. That's the point when you mustn't look.

[Note - when is the studio William would actually do this. The studio which was in Crouch End at the time was two rooms separated by a sliding glass door. William would press play in the control room and then go to the other room where there was a sofa there and sit back and see how it sounded.]

Wiliam Orbit: I've got no photographs of that studios. It kills me.

TP: I’ve got no pictures of it either. What about Goldie? He recorded ‘Terminator’ there…

Wiliam Orbit: Yeah. He did. What he did was he worked upstairs in the back room at the house. It was the guys from Sugar Dog.

TP: John Gosling…

William Orbit: Yes. John Gosling and Fritz Catlin were up there and Goldie would come around every day. And it's funny because he'd open the door and he would literally run up the stairs five at a time. He was so, so passionate about this music he was making. Goldie was a funny character.

TP: So look just to round this off… I was reading this brilliant Paul McCartney interview in the New Yorker and he discusses something he calls ‘wisdom art’ which is basically art he couldn't have produced when he was younger. So you kind have a legitimate justification for continuing to create. Even thought you’re a lot younger than McCartney what’s your take on that as sort of someone that's still making music that's relevant now.

William Orbit: Well you have to really want it because it gets harder. It gets harder as you get older, you know, and we are in a young game. It's very alluring the sound of youth. You can hear the sound of youth… You hear it and it's wonderful. But I mean, jazz musicians go on playing jazz until they drop and it’s the same with classical composers in popular music. You'd better tap into that wisdom, those decades worth of creativity and experience. Because if not, what are you doing?

TP: All right. Cool.

William Orbit: That's great, Paul. I enjoyed that.

I highly recommend digging into Discogs and checking William's back catalogue as well as hitting Spotify to follow and stay updated with the new releases he's working on. A new album is in the works...