Dubplate Sufferah

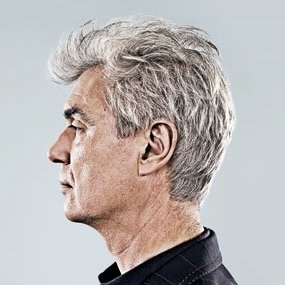

An Interview With Dennis Bovell

Part One

Emma Warren interviews the UK reggae legend that is Dennis Bovell.

Dennis Bovell was born in Barbados and moved to England when he was 12. At school in Wandsworth he discovered tape looping, with the help of a broom handle, and created his own cut-up of Bob and Marcia's 'Young, Gifted And Black' with a teacher-performed trombone piece on top. The sound system top boy created Lover's Rock smash 'Silly Games', formed UK reggae band Matumbi, wrote the soundtrack to seminal south london flick 'Babylon' (check it if you can) and produced a host of post-punk gems from Orange Juice to The Slits to The Pop Group. But this interview is mostly about that forgotten area of UK sound system culture, the cutting house – the place where DJs and producers have been going to get their dubs cut since reggae arrived in the UK in the 1960s.

The full feature, by Emma Warren, contains interviews with the UK's foremost reggae historian Lloyd Bradley as well as drum 'n' bass don DJ Zinc and Jason Goz from Transition Mastering Studios, will be in the next issue of the super-fly dancehall and grime fanzine Woofah. Pick up the print version or check it online at Woofahmag.com. And you can check Emma Warren's monthly half-hour Wandering Feet podcast, featuring music from kizomba hip hop dudes Ritchaz e Keke and Silkie and interviews with William Orbit, Deadbeat and Musinah here.

People know about pirate radio and all that, but they don’t know how important cutting rooms were. Do you agree?

Without cutting rooms we wouldn’t have had what we had. Cutting rooms are most important. The transition of the music, from the studio to the turntable.

How did you discover cutting houses?

About the age of 15 there was a recording studio built in my school in Wandsworth. The school was called Spencer Park, then it was renamed John Archer after the first Mayor of colour, and since completely abolished. The site where it was, directly opposite Wandsworth Prison, was a hospital during a time of war. Then it became a school. There was a bell tower in the building which was turned into a studio. Our school had a thriving orchestra, a thriving drama group and it was positively one of the best schools in Wandsworth. The studio wasn’t built for the drama department, it was built for the English department to record plays. At the same time, I was involved with a group of lads and we were called Roadworks Ahead. We helped ourselves to quite a lot of the Government’s gear, to adorn the stage when we played a gig. The headmaster made us take them back. I’d made friends with lads that lived down the end of my road, and lads who knew I could play the guitar. Norman Hitchock, Colin Short, Derrick Chandler and me: that was Roadworks Ahead. The studio was built and one day I hit upon an idea to make a loop. This involved recording a piece of a popular reggae tune and editing it together so it went round and round constantly in a loop, with a broomstick to keep the tension on the tape recorder. I created a loop from what was the number one reggae tune at the time: Bob and Marcia’s Young Gifted and Black.

Was this a new idea for you? Or were you inspired by other people doing it?

No. I had the idea. At this time I was messing around with tape recorders. No-one had done it before as far as I was concerned!

This was when, ’67, ’68?

Yes. I was a kid of 14, 15, playing with a tape recorder, in charge of the school recording studio. But I was also a musician and I suddenly had the ability to tape from disc on to this tape. I brought in my copy of Young, Gifted And Black and realised there was a bit of the song where they weren’t singing, so if I took that I could then make my own record without having to have a band and no-one would know where it came from.

How many bars did you have?

Two bars.

I thought you were going to say six, eight…

I took two bars of that song and I made a loop. And in order to make it play without going whrrrrrrwhrrrr (does wonky time sound) I needed tension. An old Ferrograph, it was. A broomstick came in handy to steady the tape. Then copying that onto another reel… we were blessed, we had two tape recorders, just ¼ inch two track tape. You’d have to mic the whole band up to record it – we did that as well – but for this purpose we didn’t. That record is why I became known as Blackbeard the Pirate later on, because I’d done this in my school days. I invited members of staff who played trombone and flute to join me in my adventure and to play a trombone version of a very popular song, Guantanamera. To be marrying that with Young, Gifted and Black! I did that.

I guess that makes you the original fusion man. So how did this record lead you to the world of cutting houses?

It was customary for sound systems to play dubplates. Except in those days they weren’t called dubplates, they were called ‘wax’. I took it to the local cutting house, which was owned by R.G Jones. Now R.G Jones is one of the most reputable studios in this country. It’s in Wimbledon, right. And old man Jones, he’s long passed away now…

Reputable how?

Cliff Richards recorded there. The first black group from Scotland, Average White Band, their first album was recorded there. Mutumbi’s first recordings were recorded there. RG Jones were the first people to have PA Systems. Old man Jones was intrigued by this school boy who was cutting wax.

How did you know about him? Did you know about cutting houses generally?

It was probably the Yellow Pages to find him. It was Wimbledon and I lived in Clapham Junction so it was the closest one.

So he was intrigued by what you’d done?

I didn’t tell him what I’d done! But he was intrigued that kid of my age wanted to cut an acetate. So he explained to me about the frequencies and the cutter head and I made this acetate and sold it to this soundsystem called Jim Daddy. It must exist somewhere. It was the only one I made. The only other person would know about it was the teacher who played on it, he was a young one so he’s probably still alive. I’d like to find that man again.

So the tune went to the sound systems. And…

From thereon in, I was doing that kind of thing.

Now you had a place to get the music out.

I had a place to get my wax cut. And an outlet. The first one we did, we sold it for £3. In 1967 went a long way. It was a lot of money! A lot of people were getting £3 a week.

What were cutting houses generally like?

After that I found another cutting house, owned by a man called John Hessle. John is the architect of dubplates in this country right across the board. He was less expensive than RG Jones. He was cutting in mono, so it was the same on each side of the record. In fact, a lot of my stereo tapes were melted down into mono by using him, but sound systems were largely mono anyway. So it wasn’t that bad cutting a dubplate for a system on a mono lathe. He was an old Jewish man and they had a lathe in their front room in Barnes.

Another person with a cutting room in their house…

Another person, yes. RG Jones was a proper studio. Hessle’s was in his house. In Barnes. In Nassau Road.

What was the picture when you knocked on his door?

First was ‘what was this black kid doing in this neighbourhood’. John was blind, he’d been wounded by shrapnel and he lost his eyesight but his hearing improved. He had this mobile recordings business. I went on mobile recordings with him as a youth, to record Jaspar Carott. Before he was big on TV he used to record for a label called Sweet Folk All. Sweet Folk All! I’ve got loads of Jasper Carott records from before he was famous. Once I went with Hessle to the Royal Albert to record the Latvian Song Festival. A 500 voice choir no less! And John, he was a neighbour of David Rodigan. I met Rodigan then, before he was Rodigan the DJ, when he was Rodigan the actor. He did one of the first Guiness adverts on TV. Way way waaaay before he was Rodigan the DJ. He was curious what was going on and John Hessel would slip him acetates and he got to meet Shaka, everyone else.

Who else would be there?

Me, Sufferah. Shaka. Shaka would be camped out there all day. Be using the cutting room all day and no-one else could get in, then John would get pissed off ‘I’m not cutting any more tonight, this is my home!’

Shaka was in there, no-one else could go in. So where do you wait?

In the street, van loads of black people, the neighbours going (puts on posh voice) ‘what’s going on dear?’ I didn’t wait in a car. I was the first person, one of the first people, to go there and word spread. I was there before Shaka, before Coxone

So what did these cutting houses do before? Were they linked to soundsystem culture?

Not at all. They were tape to disc. Ordinary transcription service.

So the people who came from Jamaica, who were cutting dubs for their sound systems, where were they going?

John Hessel told me himself that he was intstrumental in building the Treasure Island studio. He was a friend of Duke Reid in Jamaica, before Duke Reid passed away. This was a Jewish guy, a white guy. I owe that man a lot, for taking me as a young man and telling me about the frequencies. He was instrumental in guiding me in how best to put the frequencies on so they reproduced properly. He was afraid of tripping the cutter head. You’d have to send to Germany for a new one and that cost wong. He wasn’t about to trip that for a dubplate for some young black boy. He’d send me back to the studio to remix it if my treble levels were too high.

I’m interested in the fact that cutting houses provided a sort of schooling…

It happened for me from talking to the cutting engineer. He’d been alive during the war, enough to be blinded. Him an elderly man, me a teenager. Whatever he said was gospel. If John said it, I had to do it. By this time I’d moved away from looping and moved into recording. I was recording with Matumbi and engineering. I’m interested in placing microphones and all that. I want the best for my product and I want to sound as heavy as the Jamaican stuff. And John was the best man to talk to.

Part two follows soon.

[Emma Warren]