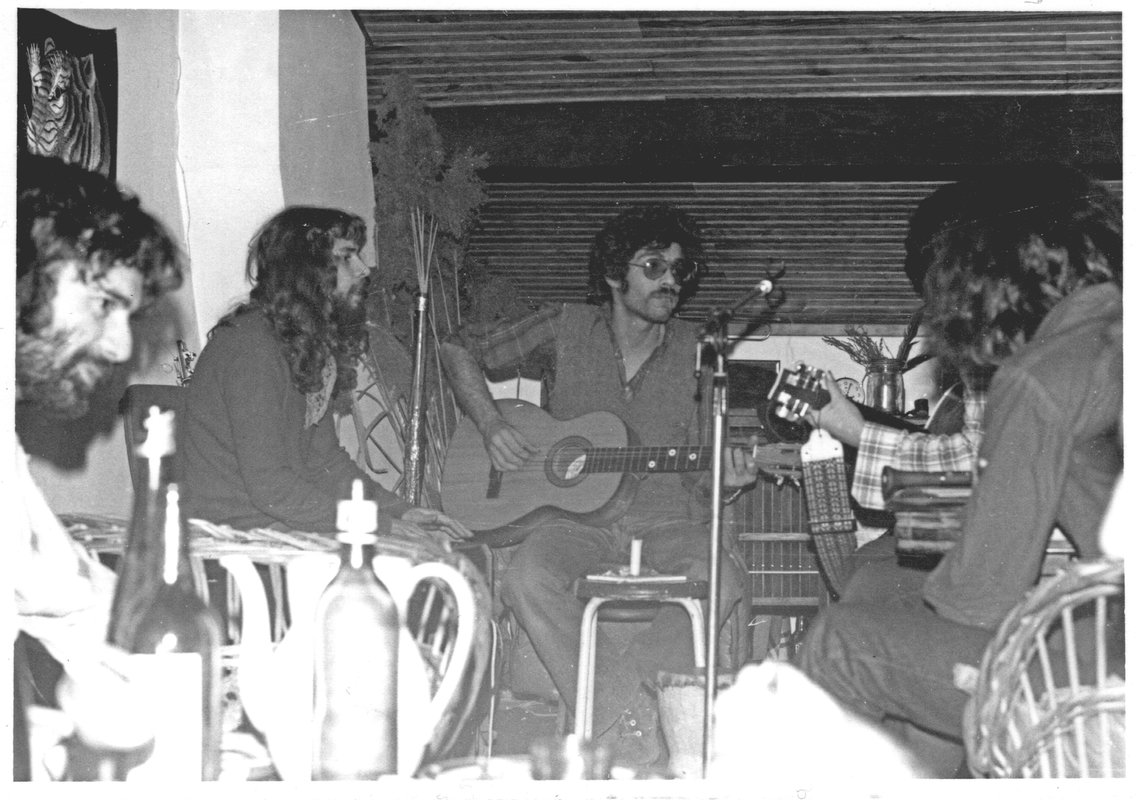

“Any Lebanese person who lived in Lebanon or grew up here will always have the sadness, you know, or this melancholy or nostalgia to something,” says the cult Lebanese singer-songwriter, guitarist and producer Rogér Fakhr. “This is something you carry with you when you're born there. It has a culture to it, and it has a feeling or an emotion that's very different from anywhere else.” This feeling or emotion runs rampant throughout Fine Anyway, a new compilation album of material Fakhr wrote and recorded in Beirut and Paris during the 1970s.

From the hiss-soaked folk-rock of ‘Lady Rain’ to the lush, West Coast AOR of ‘Gone Away Again’, Fine Anyway’s seventeen songs portray a yearning seeker with a sonorous voice, vividly expressive guitar chops, and a spellbinding sense of composition. Short and spare as they often are, Fakhr’s psyche, jazz and soul-infused songs are portals to another era, another realm, another lifetime. Despite their striking beauty, and the respect his name holds within the generation of Lebanese musicians who came of age in the years before the Lebanese Civil War, Fakhr’s 1970s work never received the global recognition it deserved.

Last week, I spoke with Fakhr via Zoom from Los Angeles, where he has lived since the early 1980s. Fakhr decamped to California after touring the United States as a guitarist for the truly legendary Lebanese singer Fairuz and settled into a new phase of life. Over an hour-long conversation, he regaled me with an array of beautiful, sad and reflective stories from the past and his optimistic hopes for the future.

Martyn Pepperell: From what I understand, when Jannis from Habibi Funk started talking to you, you were unwilling to revisit the music you wrote and recorded in the ‘70s. What changed?

That’s right. This was forty-five years ago. In the beginning, my recordings were very folk-oriented, very James Taylor oriented, a singer-songwriter with a guitar. Then, we moved on to add bass, keyboards and a drummer for songs that were developed later. They continued to evolve, and even today, I’m still evolving. I have songs today that are completely different from what was happening then. They’re a little more socially or politically oriented, and the old stuff isn’t me anymore. So, it was kind of difficult for me to agree to just put out old stuff that isn’t me, the way I am today.

But circumstances change. On the 4th of August last year, there was an explosion at the port in Beirut. Janice approached me and said that a few of my friends had agreed to provide their songs for an album to raise funds for the Red Cross. I didn’t have to think twice about agreeing to be involved. It was kind of difficult for me to select songs for it, but we picked a couple. After that, he came back to me and said that musicians talk about me in Lebanon and that it was important for me to put out my music from that era. Finally, I agreed. Even until now, I’d like to re-record those songs, because I continue to hear them in new ways, so it was very nice for me to put those versions of them behind me.

As a listener, I instantly felt something special in the songs collected across Fine Anyway.

We did get interrupted, you know? Something was happening in Lebanon in the early '70s. We were starting to sprout, you know, we were just starting to come up. It was really a great time to live in Lebanon. When the war started, it was like, you know, somebody cut our throats or something. We just couldn't continue and something died. So we continued each on our own. We actually knew confinement way before COVID. We confined ourselves literally to a house as musicians, and the music never went out.

Just before, you were talking about how you were a different version of yourself when you wrote these songs. Do you think you were asking the right questions at the time?

Absolutely. The songs are still alive. For me, I still feel exactly the same way. There’s some kind of theme, which is really contained in the sentence, Fine Anyway. Some of the song’s titles speak for themselves. Sometimes you feel bad and there is nothing you can do but keep going. There is a message there, whatever happens, you don’t always have control. Very often in life, things happen to you, and you have to just get up and keep going. There’s nothing else you can do.

Some other songs are just illustrations. They’re a picture of a moment in time if you will. Some little blues like ‘Insomnia Blues’ or a little love ballad. Some of the others are just fun. I keep singing them. For me, they’re not dead, but I changed my view on what the songs are.

Can you walk us through the compilation?

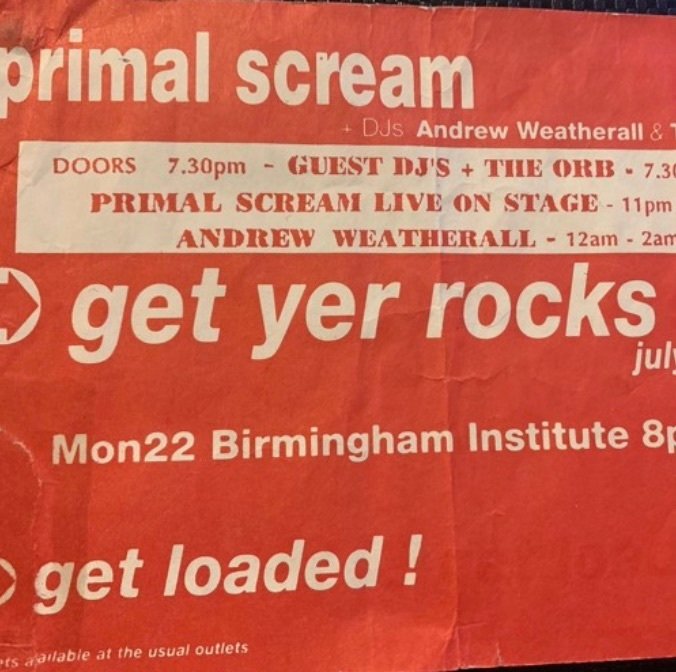

It’s made up of three very distinct sets of recordings. The first is ‘Lady Rain’, which I recorded after I won a televised competition for singer-songwriters in Lebanon. They had various categories. Singer-songwriter, interpreter, instrumental. Lebanon was very international, so they also had Arabic, English, french. I just went for the singer-songwriter part and won. I also had another song called ‘Spending My Time Drinking Tea’.

After that, before the war started, I was travelling all across Lebanon writing songs. I was speaking with friends, learning new guitar chords and all this. This was when I wrote most of the second part of the compilation, Fine Anyway, which came out on cassette. We had two hundred cassettes made, and we made the covers by hand. I drew the cover for all two hundred copies and made the design as simple as possible, so they all looked the same. Most of the songs on the compilation are from there.

Then you have the four very distinct songs that I recorded with a band in Paris after Fine Anyway. Those were exciting and progressive. I met with a friend in France, his name was Renault, and he had some money. We went to the studio, hired some musicians and I wrote charts for them. After this, we started recording at home with some friends. We recorded on a Revox A77 and added different effects. So, there are periods with different ideas and different ways of producing music, singing and recording.

How important do you think Paris has been to your journey as a musician?

I developed a lot in Lebanon before Paris. I had to go to Paris. It was either carry a weapon and shoot that guy you played ball with or confine yourself, learn guitar and do something else, which I did. I was forced to travel to Paris because the war was going on and I had nothing to do. I was a musician and a singer-songwriter and that doesn’t work when you have a war going on in the streets. I was lucky because my dad worked for a local airline, so I had free tickets. I went five times.

The last time I went, my musician friends from Lebanon and my girlfriend, who also sang sometimes with the band, were in Paris. That was my longest stay. This is when we really developed together as a tight community of musicians and friends. That was a completely new story for me and my guitar playing changed as a result. In Paris. I had the chance to listen to music that was coming out, that was not reaching Lebanon because of the war. Previous to the war, we used to receive all sorts of music from Europe, from the US, from Britain, etc. But in Paris, I was exposed to a lot of different music, including Brazilian music, rock, a lot of rock, Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin and all those kinds of things. It was beautiful. It’s a cliche, but Paris is an artist’s city. The buildings, the roads, the little alleyways, the people; everything really.

Did Paris shape me though? No. In Lebanon, we spoke English, French, German and Arabic. We spoke French at home and I grew up on French music, so by the time I got to Paris, I knew France. I knew French, but I was more attracted to English and American music. I never left that English mindset, if you will. I was always in the record stores checking to see if there was a new James Taylor album.

How young were you when you first started recording, and what was the experience like?

I would have been fifteen or sixteen, this was before the war. The first time I recorded was at home on a small reel-to-reel. I used to record myself playing the guitar and listen back. This was right before The Beatles released Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. It was so funny. Then it evolved to a larger Tascam.

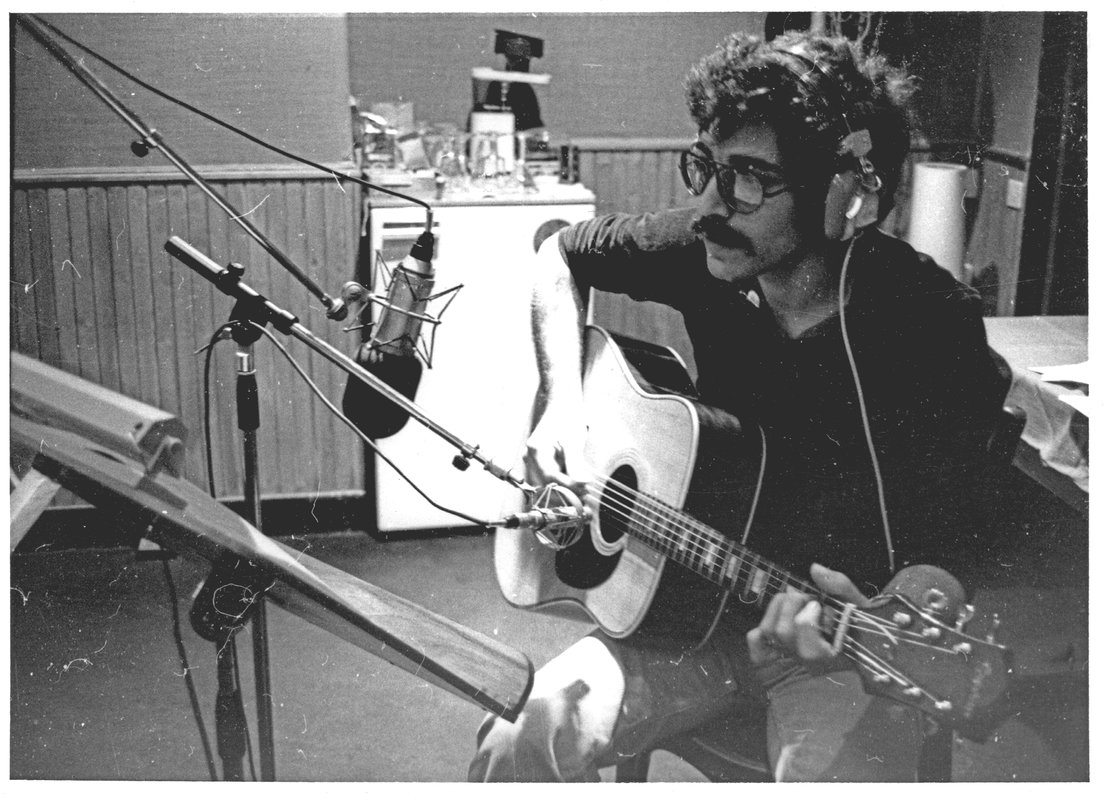

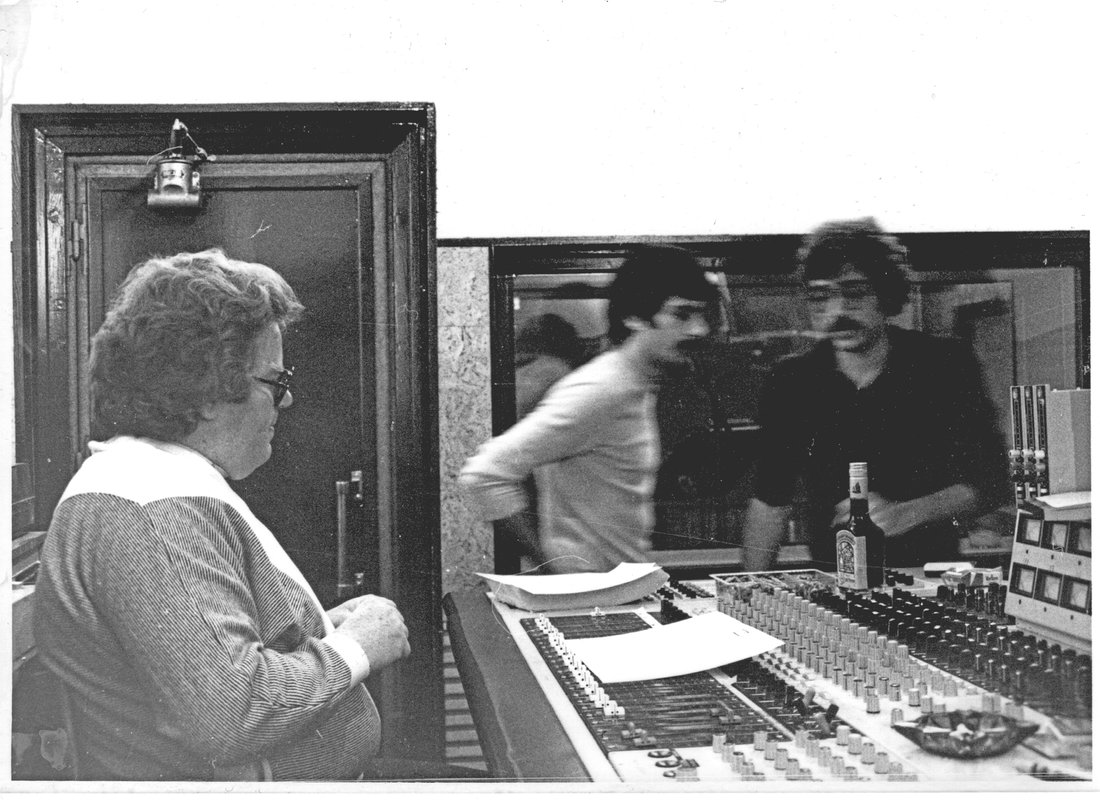

The next time when it was really serious was when somebody was recording and I was just performing. That was the music we did for the television contest. It was an eight-track studio. It’s a dinosaur by today’s standards, but I was so impressed. You know, just me there with my guitar and you can come back and add in other instruments. It was quite the discovery.

I’m sure you always had had the hunger to write and sing, but what was it like when recording became part of the process?

Oh, I went crazy. When we recorded Fine Anyway, it was in the same eight-track studio that we recorded after the television contest. It was my studio time and there was nobody else. No one could tell me what to do. I was telling the engineer what to do, and I went crazy. They had eight tracks, six or seven of them were guitars or vocals. Most of the songs have backing vocals, one nylon string, one acoustic steel string, and some kind of panning or effects. It only encouraged me to sing more. We always recorded in one day after practising the night before.

Do you think this had much of an effect on how you wrote your songs?

A song starts alone with your guitar somewhere, you know, at home, when you’re camping, or maybe you’re just driving in a car. An idea comes in, you write it down. You sit down and say, okay, I want to work on the song a little bit, I only have two sentences, you know, how can I make them twelve? Then you start thinking, I’m doing this chord, I could do this other chord, or bring the bass player in. So it doesn’t inform the songwriting, but it colours it. It affects it in a very important way. Today, these days, this is the first time in my life where recording informs my songwriting because I'm using Garageband, or Logic Pro on a computer. I'm bringing loops together and I don’t have any song in mind. I’m loop writing if you will.

We recorded ‘Lady Rain’ in 1975, Fine Anyway in 77, and the four tracks with musicians were in 1978. Then, as I mentioned earlier, during our last stay in Paris, we discovered the Revox. You can multi-track with them. So, when we went back to Lebanon, we did our best to acquire one and we started recording there. We brought in my friend who was a saxophone player, some flute, I added guitar, and we recorded a lot of songs.

What do you think the significant factors have been in your life that have shaped the music you’ve written?

I was always a singer-songwriter with a guitar. I was always like that, at least until recently when I started using the computer. It was always a relationship between me and the guitar. The song just comes. I have nothing to do with it. I just start strumming a chord and the words start coming. Here’s the first verse, here’s the second verse, stop. I never revisit the song. Most of my songs are two minutes long. They’re all short. Sometimes I think, oh, I could add a third verse here, I could work on the words because English was my third language and you can tell from my syntax, but it was always me and the guitar. The songs just come.

That said, maybe it has to do with the feeling and spirit of vagabonding, if you will, of being on the road all the time. When I became a musician, I left my parents. I was travelling in Lebanon all the time, sometimes living in tents in forests, travelling to Paris, coming back from Paris. So I spent a lot of time on the road. I think that had a lot to do with the music.

Do you like sunny weather?

The sun? Actually, I don’t. I love rain, wind and typhoons. I don’t like it. I hate summertime. I mean, I like the sun for its benefits and what it does, but I like the cold. I would happily live in Portland, Oregon, where it rains six months out of the year. When it is raining, people keep off the streets and I really like to have quiet around. I like to be alone a lot. A lot of things come to me when I’m alone, rather than outside with people in the sun.

Let me guess, you’re a nighttime person as well?

After 10 pm, the quiet time starts for me. That is when I start reading, listen to music, or try to do something; that and early mornings. When you’re like this, you stop functioning when the world wakes up. This connection, you know, this connection to another realm, it won’t happen with all the noise and too many people around. I feel extremely lucky. This thing, whatever it is, it just comes. As they say, you’re just the vehicle. You’re just transmitting something. It’s not really your life. It may be your life through your words, but it’s a connection to something completely different. Something that is not physical or material.

Periodically, you come across these people who are just flooded with creativity and can write a huge number of songs. I’ve observed that some people seem to have to develop a spiritual framework or embrace religion to make sense of the question, why me? Why can I do this?

In the ‘70s, I had this flow. The songs just kept coming and coming. Song after song. Over time, it continued, but it took a different path with different songs. It kind of switched gears, if you will. Today, I still have it to a lesser extent, but when you have a family and a job, things change a little bit. You have more things blocking you from accessing the flow, but it’s still there. I think that once you have it, it’s your fault if you lose it. It’s never circumstances, it’s never because of other things, it’s because you allow other things to impact you and take it away from you.

When I was in my twenties, I didn’t want to do anything else. In Lebanon, I lived in a really tight community where everyone helped each other and there was lots of give and take. When you live in a different country, things change. You have to make a living. I was lucky enough not to have to do anything else at the time. That was a blessing. It was extraordinary and fantastic, but then you have to do other things and they get in the way.

How do you feel about life in America since Donald Trump’s presidency ended?

In the US, you can't forget that he exists. I think he left a legacy, that unfortunately, a lot of people have decided to adopt. Now, it’s like we have many mini Trumps. It’s happening everywhere, all over the world. This me-me-me before anyone else ideology. People have forgotten how to collaborate. People are forgetting that there is something other than the Me. On the other extreme, you have all these movements that are trying to say We. I think this is a big fight right now. This is a big battle that's going on. I'm hoping it's the We that takes over.

Photography credit: The Raymond Sabbah archive.

Fine Anyway is out now in LP, CD and digital formats through Habibi Funk (Order here)