Interview

Jean-benoit Dunckel

Air

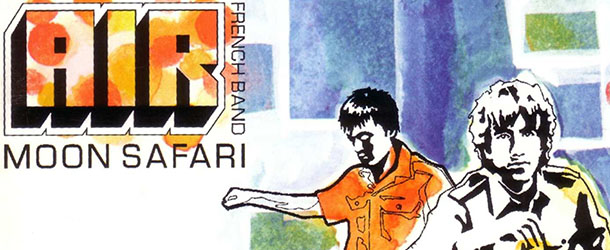

It’s bizarre to think that it’s been twenty years since AIR started releasing music. Treading lightly between Trip-hop and Lounge - breathy vocals and sanguine, spacious melodies delicately hung by the faintly remembered French Touch - AIR seduced the world with dreamy, sexy pop records and soundtracks which veered from highly intimate and emotional to energetic, anthemic and experimental.

When it’s right, a retrospective is an opportunity for the band to retread the path which has led to their current vantage point, concisely collecting the milestones and remembering the lofty peaks and low troughs of their journey. We caught up with Jean-Benoit Dunckel to talk us through what made AIR ahead of the release of their new 'Twentyears’ compilation.

TP: So starting at the beginning, how and where did you first meet Nicolas?

JB: It was at college, I think I was fifteen years old. Nicolas was part of another class, another group of people. He was doing music with Alex Gopher - Alex was a bass player and a DJ, he had grown brothers so he knew a lot of stuff about recording and everything. So he was recording with Nicolas and recording with me too but we’d never met, so he introduced us to each other and we worked together to do recordings. Nicolas was playing the guitar more and I was playing more of the keyboard and so it was going well, and we became a band, for almost three years.

TP: And this band was Orange, right?

JB: Yes. I regret not saving the name, I should have saved the name somewhere, like with a lawyer. I could be really rich right now [laughs]

TP: Could you give us an idea of what you were listening to at the time, where you were going out?

JB: Yeah I was into all the good stuff from the seventies, like I was a really big fan of David Bowie, and so through David Bowie Iggy Pop and Lou Reed. Also German Krautrock music, I discovered Kraftwerk and Cluster, and NEU!, and then bands like OMD, you know the band from the eighties... we were big fans of the Cure, big fans of Sisters of Mercy, big fans of Joy Division and New Order, Depeche Mode, this kind of stuff

TP: And this was all while you were studying in Versailles?

JB: Yes around ‘87

TP: And that’s when you became close

JB: Yes we became close, we were recording all the time, and Alex Gopher was very important because he had all these records from his brother – he was like a Mod, he was into scooters and into parties, he was a DJ and was really good at recordings and so we borrowed some tape recorders and we started to record and to know about recordings, you know. So Alex later said there was something incredible, a new machine, it was a sampler, and so with the sampler we began to do loops, rhythm loops, and around this time Nico and me were not working anymore together because he was doing his studies in architecture and I was in a science university, and it was far away and it was different worlds. But when we met again, Alex had taught Nico how to use a sampler - I didn’t have any money so I couldn’t buy a sampler but when we met again to do the first AIR records we had a sampler to record beats and so AIR was like, you know, loops. We screwed beats and some keyboards and guitars on top of it, and that’s how we started.

TP: So, Orange. This band seems pretty elusive, mysterious – I’ve tried to find recordings online but there’s nothing anywhere...

JB: There are but they’re at home...

TP: So who was actually in the band?

JB: Who was in the band, oh, well it turned, there was different people... but there was like, me, Nicolas, Alex Gopher... and there was also Xavier Jamaux, he’s a musician too, he’s well known, he had a band called Bang Gang [actually Bang Bang] - like the band of Bardi Johannson who I do music with [as Starwalker] so they actually had the same name [laughs] – and yeah he was a good drummer. And there was also Jean [de Reydellet], Jean was the singer of Orange.

TP: I’ve read somewhere that Etienne De Crecy was part of the band?

JB: Yeah he was, he was around... but he was, like, no, not in the same band. But we were doing shows together, and he was really important too because he was really the first one to say ‘alright now I’m going to do some new music - I’ll forget the pads, I’ll forget the bass, I’ll forget my instruments, I just want to do house music’, and he started with Philippe Zdar Cerbonschi – Philippe Zdar from Cassius? - and they met at this amazing studio which was really important for all the history of our dance music. The studio was Studio Plus Thirty [Studio +XXX ] in the nineteenth arrondissement. Etienne became the first one in the place of the recordings in Paris because he was an assistant and he became a sound engineer and he taught us all these things with machines. So Alex and him started really, really quite early to do recordings and to do house music. So we entered into his window, they started one year before us. I mean, Etienne had already released his first house records with Motorbass, you know the band Motorbass? They did a record and when I started to do music with Nico this record had already been released, and it was like the first new French house music record. And through house music some bands appeared like Daft Punk for example, and there were other labels and we all started together. I could hear Daft Punk’s music through the window because they were so close [laughs].

TP: How did you end up working with Source, the label that put your first singles out?

JB: Because I joined Nicolas again and we did this EP ‘Casanova 70’, and Casanova 70 went out in England and Nico had a friend called Mark working at Source and so this EP was released on Source and on Mo’ Wax in England. So when Source listened to the band they said ‘yeah you should do remixes’, and so we started to do remixes as AIR. And we incorporated the voice into our music because it was remixes, and then when Source listened to the first remixes they said ‘OK, we want to sign you because we think you are a band we want to do together’. And so we signed the contract in October, actually the 16th of October 1996 – I remember the day well [laughs]

TP: So how important was that label to the scene that was happening at the time?

JB: Yeah. Yeah really important – it did this compilation called Source Lab, there was Source Lab one, Source Lab two, three. On the first there were bands like Daft Punk, Cassius, AIR, all the musicians that became important in the future were there, with different names, and it drew the line of the future. Source Lab was a division of Virgin and so Virgin, when they heard Daft Punk for example they signed Daft Punk and released an album and when it was released it was such a success... so before that, the AIR records in England were on Mo’ Wax, James Lavelle’s record company. We went there, we did the remixes, we did Moon Safari and we went to Mo’ Wax to listen to the music and they liked it very much. James Lavelle said ‘yeah, it’s going to be huge, I love it’ and there was an assistant next to him, and he was almost dancing – but he had really a strange face on him, he was smiling, really glad but he was thinking about it. Like, he was not feeling very well but... shutting his mouth like he had something to say. So we had lunch with James then we said goodbye, went downstairs and ordered a taxi and the assistant came with us. He said, “you know, the album is amazing but the label [Mo’ Wax] is bankrupt – don’t sign with us otherwise you’ll spoil your success”. So we said okay. We waited and then Aurelie, the marketing head of Virgin London, she said “yeah I know that AIR can really really be big in England” so she convinced the staff to put some pressure and some money on the band, and one month later we had a big meeting with Virgin, like with ALL the staff, and they said are you okay trying to have success and to tour and do promotion because it’s going to be hard, you know? And we said yeah, all right. So after that, for six months or nine months we became slaves of promotion, travelling all the time, doing interviews all the time, and we made AIR meet the world, actually. It was really hard because it was not music it was just blah blah, bla-blah blah, all the time, and we became AIR.

TP: Do you feel it was an extremely quick ascent into the public eye and fame? How did it feel whilst all of that was going on?

JB: It was a strange time – on one hand I was very happy but on the other hand it was so much work and so stressful that it was not something that I really loved. I loved it later – two years after when we started to tour and to meet the audience. The best part of doing music is to be on stage and to play for people, otherwise it’s only numbers. Numbers on your bank account. Numbers of sales. Numbers of interviews, numbers of - there is no quality, it’s just quantity. People judge you on the quantity that you do and didn’t really appreciate it until much later, and I didn’t realise we were like so big. I mean I couldn’t believe it, it was like a dream becoming true. It was really strange.

TP: So turning towards the new compilation ‘Twentyears’, how did it feel going back and collecting the tracks? Would you go back and listen to these records normally?

JB: Yeah it was enjoyable to revisit it. Normally I don’t listen to AIR anymore. I listen to it when I make it but not when it’s done. So yeah we had to choose some tracks but we knew the best, we knew the strongest ones because of the reaction of the public through the stage and through the sales, internet activity, we know what people really like you know. So it was kind of easy.

TP: It’s quite striking how concise the personality of the band is, throughout the twenty-year span that the tracks cover on the collection, there’s a massive array of influences on display, genres, production techniques – and yet it’s quite difficult to pin a date on each track just by listening. How do you think AIR grew as you went on? What changed?

JB: I would say that when we started in 1997 we were already really up to it, we were really like, uh, at the top already. Why? Because we were 27 years old and I started music when I was three, and then trying to do songs when I was four years old. So at 27 I’d done a lot, a LOT of music already, and I was playing piano all the time and I’d done a lot of recordings so it was not like discovering what a song or music was, I’d had so much failure brought with me so I was really ready to try and do the best. But I think we improved a lot in music production, which is how to put your music from waves on to the tapes and to produce it. We had the chance to be in an area where the digital world was arriving but we were mixing analogue and digital. So I think we improved a lot in the music production – I think the top of this arc was in 2004 with Talkie Walkie. So in Talkie Walkie you really feel like there is this different world, analogues, acoustics, digital, working well together with an incredible sound, an incredible mix. It was really more like a sort of charm.

TP: Do you view the work you guys have done for soundtrack and sound design projects as operating in a different sphere as your albums, like 10000 hz and Talkie Walkie?

JB: Yeah I think it’s sort of a discovery about poly-diffusion with different speakers, like with Music For Museum [recorded for Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille]... we had like an amazing, big, castle room, this museum, and we did the music so it would be going through eight speakers, so that’s why we attached all the others because the notes are turning, and we worked with an experimental office in France called the GRM that do plug-ins and they are really good [with] special effects – and so we worked with them to do some music but in a special, to do like possible effects with the speakers and that was the point you know. It’s an experience.

TP: I love that record.

JB: Thanks!

TP: Have you got any plans to continue doing soundtrack and sound design work?

JB: No, not with AIR no.

TP: Something you might do on your own?

JB: Oh yeah, I mean, I’m doing a lot of things on my own. This last week I’ve been in Cannes because I did this movie soundtrack called ‘Swagger’, and I’m working on my solo project Darkel. I’m also doing some experimental shows with video artists and I’m playing keyboard on stage with a big screen and incredible images.

TP: It’s nice to hear all of the rarer, lesser heard tracks on the second disc of the compilation, collaboration is obviously an essential part of your work whether it’s with Sofia Coppola, Nigel Godrich, all of the tech guys which helped build your studio and record your records. Could you tell us what’s so important and rewarding about collaboration for you?

JB: I mean I learnt so many things from the others, for example from Nigel Godrich who is an amazing producer, and Beck also when we recorded with him, we met his friends, his musicians, and we played together and it was such a big music lesson. The fact that to play with other musicians, to try viewing something in some unexpected way and I love that. Especially with Beck it was great because we were in LA and met all these different producers and different people – we met all the Los Angeles musical procedure how they do to make music.

TP: Could you single someone out who’s had the most profound impact on the way you make music?

JB: Mmmm... it’s not easy to say... except Nicolas! [laughs]

TP: Good answer!

JB: And I think maybe Nigel Godrich...

TP: Because of his recording techniques? The approach to writing music?

JB: Yeah just like the way he does, I think Nigel knows about recordings, he knows really well how to record a guitar, he has some some really precise ears for example for the timbres and for the tones of instruments. What I learned from him is where there is a problem in a song don’t spend your time on a computer trying to fix it - just re-record it. It’s a musical problem, it’s always a musical problem and it’s always when something is wrong you just have to re-record it and find a new thing, you know. The computer is just a minute of fun. Music is made by humans and it’s made for humans and so the computer is just an interface. I learnt a lot about the acoustic thing you know, about guitars, voices and how to record them.

TP: Do you have anyone else in mind you’d like to work with?

JB: Not only within music, because I think I have the resource, the energy in me to transform my way of doing music, but to change the way I do things I would need to collaborate with people in videos, in images, I don’t know, maybe like in digital art? It’s changed so much, I did some music with a Canadian girl called Sabrina Ratte – she’s doing some amazing videos and this kind of thing you know. Collaborate with people in image.

TP: Finally, it seems you haven’t appeared with Nicolas as AIR since 2012 – I mean you appeared solo with Roedelius last year at Silencio but as AIR you haven’t performed for four years?

JB: Ah yeah that’s true! But I mean Nicolas wasn’t there [at Silencio]. I was alone. [laughs]

TP: Are you looking forward to coming back and performing this year with Nicolas? What can we expect from the shows?

JB: I mean, the shows are going to be like a compilation of all the best AIR tracks, and we’re going to have amazing lights behind us, and all of the AIR spirit exploding on stage. It’s just like the best of what we can do [laughs]

AIR will play at Field Day and Secret Garden Party in the UK over the summer, and have loads of other appearances in Europe and further afield lined up too. Their 'Twentyears' retrospective is available now from all good record dispensaries.