Interview

Nick Logan

Publisher & Editor

The Face

Smash Hits

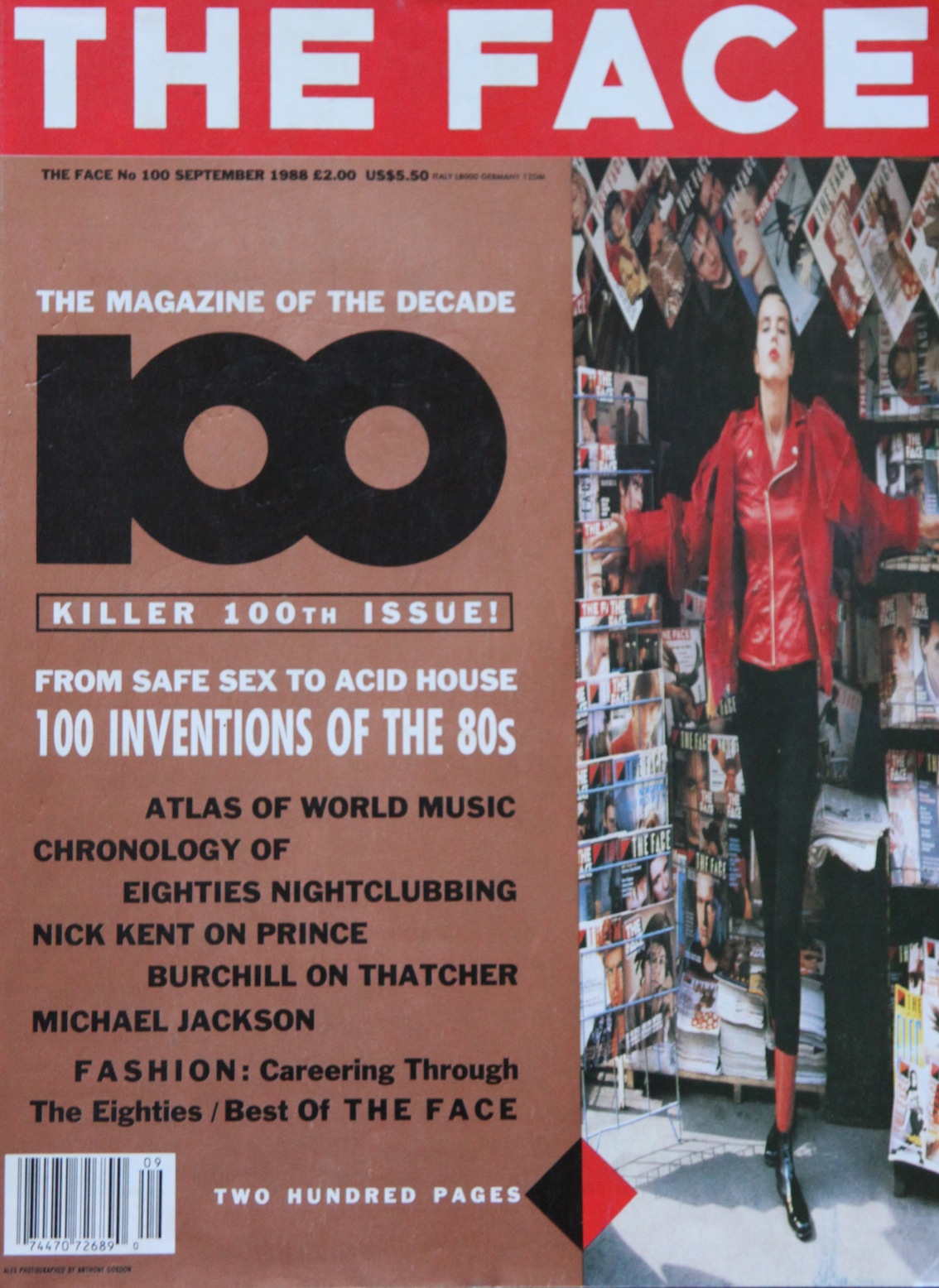

Any regular readers of Test Pressing will know I am a big fan of The Face. For me they covered youth culture in an intelligent way at a time when the culture itself was vibrant, colourful and exciting. The man behind The Face was Nick Logan, named the most innovative magazine man of his generation by The Guardian (listen to their interview with him here) and an afternoon talking with him over a few glasses of wine was pretty much the perfect way to spend a few hours. Logan has quite a history. He sat as Editor during the halcyon days of the NME, where he ran an infamous ‘Young Gunslingers’ ad which brought Julie Burchill and Tony Parsons to the paper. He created and set up Smash Hits, the magazine where Neil Tennant of the Pet Shop Boys was Assistant Editor for a period of time, and that also launched the careers of Mark Frith, Mark Ellen and (our favourite) Miranda Sawyer. He then moved on to set up The Face, and in turn Arena (amongst others), at his Wagadon publishing house. He has ticked all the boxes in the world of magazine publishing. The Face was the reason for our meeting to find out why he set the magazine up and what the landscape was like in those times.

What were the key things you learned from Smash Hits with regards to setting up knowing what you wanted to do with The Face? Was the time focusing on the younger market with Smash Hits the perfect time to generate ideas and a need to create a publication that appealed to an older audience?

When I left the NME I really didn’t know what I was going to do, I just had to get out for my own health, but I knew I didn’t want to work for a corporation ever again. I thought I might be able to form some kind of relationship with a smaller publishing company, one in which I might be on a more even-footing financially. I was poorly paid for all the stress that came with the job of editing what, for IPC, was a huge money-maker.

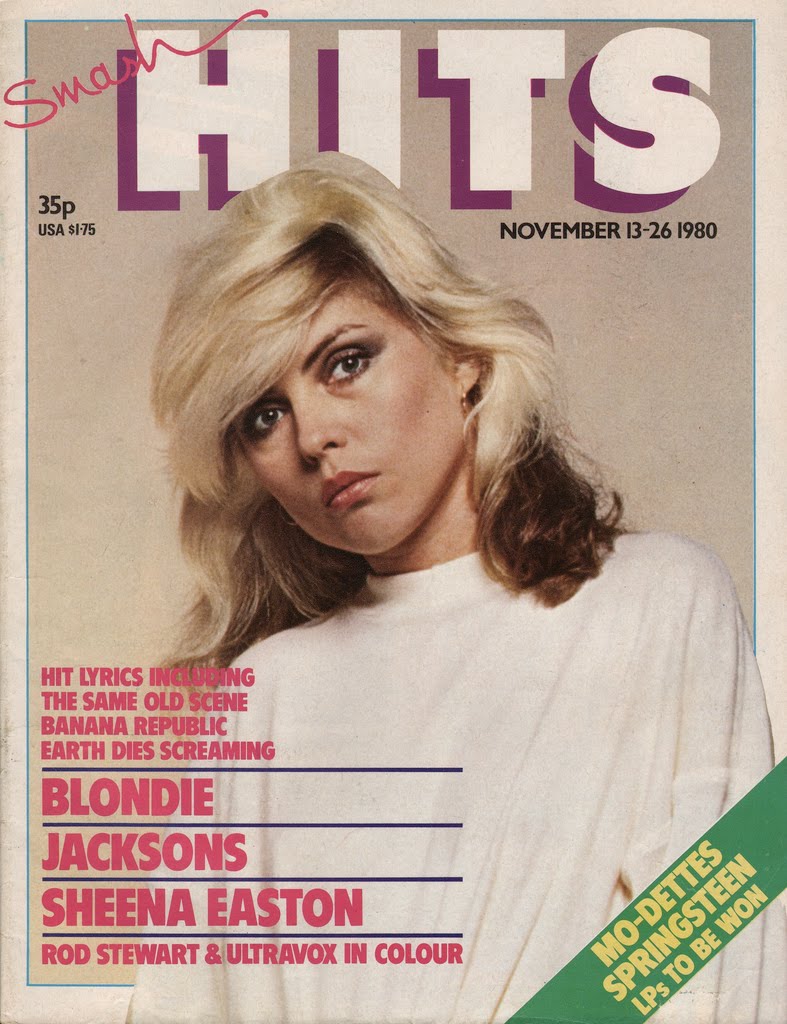

Smash Hits happened almost by accident. I’d come up with three/four ideas for music magazines but I didn’t want a potential publishing partner to think I was simply offering them a rival to NME - that was never in my mind. So, to widen the range of ideas, I threw in a teen song-lyric mag based around improving on a pretty poor existing title. I was surprised and thrown by EMAP’s reaction: the teen magazine was the one they leapt at.

So it was a diversion to proceed down that route, and not one I particularly embraced at first. I worked up the first two/three issues, just me working from my kitchen in E11, couriering pics and layouts to EMAP in Peterborough. It was almost immediately a success. EMAP then found offices in Carnaby Street, ironically directly across the road from the NME. I edited it for a year or so – with other staff by now of course - but it was never something I wanted to do on a long-term basis.

What I discovered from Smash Hits was the joy of working with a small team after all the hassle at the NME. And also working for the first time with colour photography and quality paper stock. Every other teen magazine at the time was printed on cheap newsprint with piss-poor reproduction. I made clear to EMAP that I wanted good paper. They did a test issue, distributed around the North East, using 90gsm paper (most quality mags are on 70 or 80gsm) because they had stock left over from a previous job. Pretty much every respondent said how much they liked the quality and, to their credit, EMAP stuck with the expensive stock.

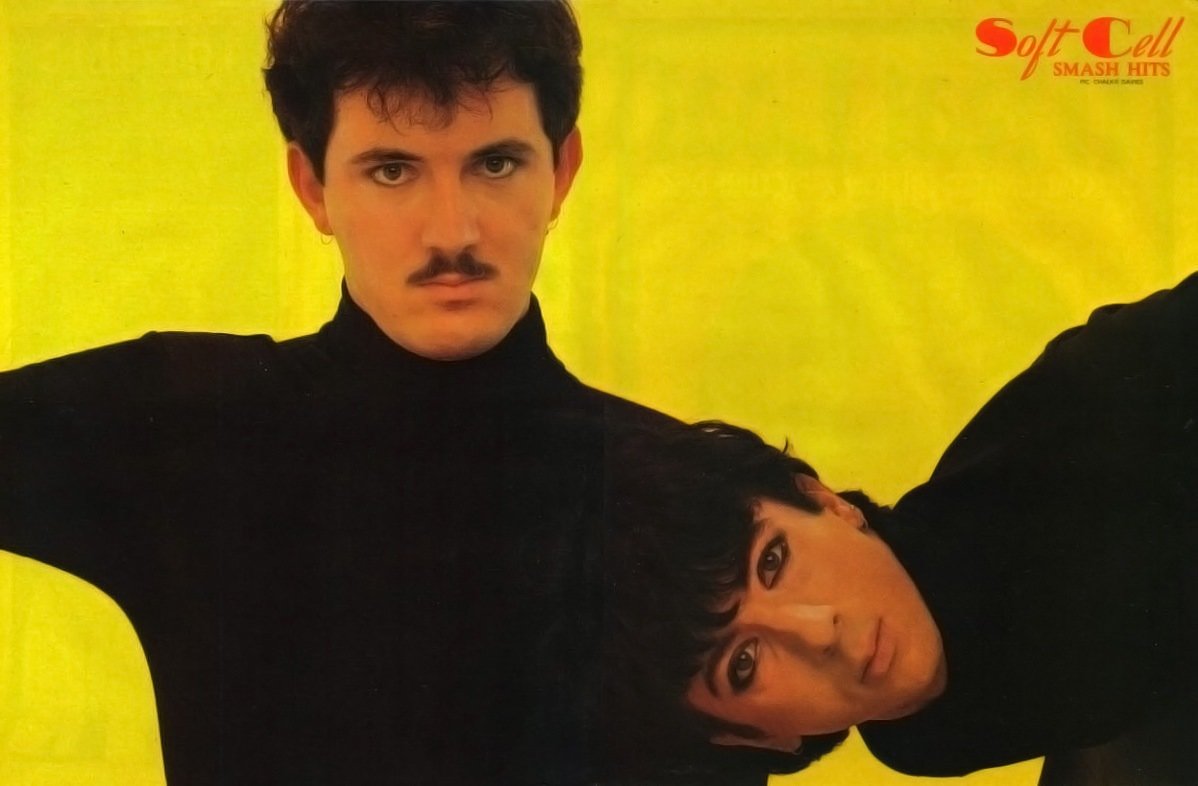

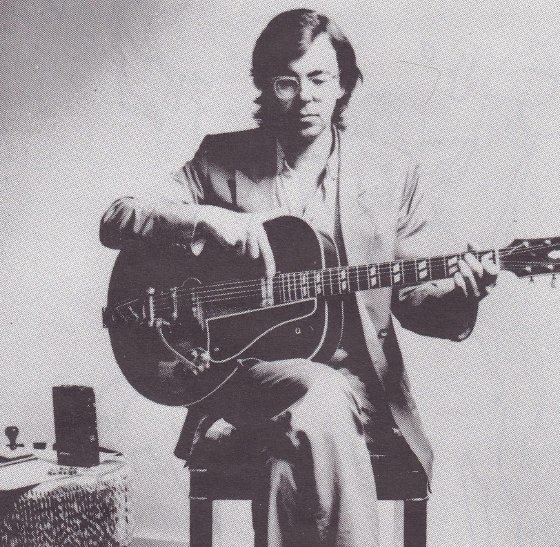

When I started The Face the photographers I used were people I had discovered through Smash Hits - like Sheila Rock who did brilliant colour photography and she pretty much did the first-ever fashion and style pictures for us. And others like Chalkie Davies and Jill Furmanovsky who shot for the NME, and gave me out-takes in black and white and shot for me in colour. Previous to Smash Hits and The Face, most photographers colour work would have been for foreign magazines in the US and Japan. The production qualities of The Face and the paper quality were major draws for the photographers. And also for writers: they loved the way their work was presented – especially when Neville Brody came in as Art Director.

What I wanted with The Face was have the production qualities of, say, Tatler or Vogue. It was kind of, Why should the devil have all the best tunes? Let’s have that quality with this subject matter historically only ever seen before in grainy newsprint. So I learnt a lot from Smash Hits. I can’t say I really learned the business side as I never really took much notice of that aspect of publishing either on the NME or Smash Hits, but I saw how successful Smash Hits was so very quickly and I hoped The Face would emulate that … but it didn’t. Instead it was a long haul to success. Another important lesson from Smash Hits … it validated my theory that most of the bands the NME covered - acts that had commercial potential and integrity, everything from The Clash to The Jam to Blondie – also held appeal for a younger audience. That hardly seems a revolutionary statement now but you have to remember there was barely any coverage of rock or even pop outside of the narrow music press. Frankly - and I told EMAP this when at one point they proposed the title ‘Disco Fever’ - I was only interested in doing Smash Hits if it covered primarily the kind of acts that I believed in.

What were your initial hopes for The Face?

As I said, I hoped it would take off like Smash Hits. At the same time I knew I had to be prepared for a flop. I had no idea which way it would go. There was no market research, I was acting purely on instinct. In the event I was unprepared for the arduous, frustrating and scarey first couple of years of The Face’s existence.

So you must have seen a gap in the market for something that covered culture more intelligently?

Yes I thought there was a gap in the market , and that was for a publication I would want to read myself. That’s been my philosophy on everything I’ve done, everything that’s been successful that is.

And that ‘gap’ was for a glossy magazine that acknowledged the fashion end of music, which was always important to my mind, and that was kind of what I wanted for myself almost from the time that I was 14/15 when, having left school prematurely, my mother moved out of London to live in Lincoln where I was marooned for a whole summer at the time when youth culture and the Beatles and the Stones and American Soul was happening - Tamla Motown and Chess - and there I was, stuck in this back-water (apologies to Lincoln). I was reading Alan Sillitoe and David Storey, hanging around the small modern art section of Lincoln Art Gallery, desperately trying to make a connection with a culture that was developing elsewhere.

I was desperate for knowledge but had to scratch around for scraps . Mainstream music papers were only interested in chart acts who were predominantly pop/white. As a proto-Mod, I was into black music – soul, R&B, Blues – but looking to white pop acts for fashion. One of the weeklies, Record Mirror started a tiny, 200-word series called Great Soul Heroes or something, Solomon Burke this week, Otis Redding next …. Then, maybe in something like Beat Instrumental, there’d be an offstage posed pic of the Stones where you could study their haircuts, Cuban heels, leather coats… That relationship of music and fashion always fascinated me. That pic would only have been in Beat Instrumental because it was a free PR shot. Most of the music press used live shots because the editors thought that best caught the excitement. The posed photo (outside of the cheesy PR shot), believe it or not, was a rarity – the unposed, informal offstage shot so familiar now… it barely existed.

One of the first things I did at the NME was to drastically reduce the live photos. They did little for me – so many of them were clichés.. I didn’t want to see Roger Daltrey’s tonsils; his jacket was more interesting to me. . Paul Weller walking through a crowd of Mods on the way to a gig … that was a far more interesting to me. So I had pushed this way of photographing acts when I was editor of the NME and I wanted to develop that, now using colour as well as black and white, at The Face. In that field, at least for a male audience, there was no one else doing it.

How did you get the initial funding together - I read you mortgaged your house?

No that’s not true (laughs). I just read that as well. Where did you read it?

On a website about Lincoln funny enough...

I just read that in Graham Smith and Chris Sullivan’s ‘We Can Be Heroes’ book. They say I mortgaged my house to get £12,000 together to start The Face but it’s not true. I had two young kids to support and would never have taken that risk. No, I had £3,500, or around that, of savings from Smash Hits payments and royalties from my part in the ‘NME Encyclopedia Of Rock’.

So how far does that go?

Well it went far enough to get one issue out. What I did was - I worked out that provided I hit a certain level of sales, and I think the target was around 50,000 which was feasible, then I would be able to pay the paper, print, typesetting (which was a separate bill then) and the contributors. It would stretch me but I could just do it if I got to 50-55,000 sales. I never asked anyone for money. I didn’t know how to present myself to a bank or anything like that. It wouldn’t have occurred to me, and my dad had gone bankrupt, so it was a case of, this is the money and it has to cover this issue and it must have covered a bit of the next one as well. Amazing to think that £3,500 would get you that far.. Don’t know what it would cost now but I printed 75,000, which is a lot, especially launching as an independent publisher, and I sold 56,000 which was exceptionally good. I had one ad planned, that was the limit of my budget, and it was going in the NME. But the NME then went on strike, and the absence from newsstands on NME and Melody Maker definitely helped me initially on the newsstands.

Where did you sell it through initially?

Through mainstream newsagents nationally. I never wanted it to be a small-circulation magazine sold only in the ICA, Selfridges, Rough Trade. I didn’t want a ‘parish magazine’, for want of a better phrase. The whole point was to get something out in the mainstream, which was a double-edged sword as it turned out. I love i-D, but i-D took a different approach. They launched nine months after The Face and I imagine they started off with a print run around 20,000, whereas I wanted to be out there with all the other magazines, competing with them on equal terms. I also signed up almost immediately to have sales figures audited by ABC (magazine auditors who verify circulation figures) and that’s the double-edged sword because they are watching you all the time. If sales figures dip you are deemed a failure, never mind the underlying demographic. Sales figures can only go up and, of course, that’s impossible so it puts publishers through all kinds of contortions to maintain sales. I am not sure many of the style magazines now are ABC’d. So it was meant to be a proper magazine, audited like all the others, and I wasn’t even trying to get much in the way of advertising at the start so I don’t really know why I signed up to ABC. It wasn’t until about 14 months in that I realised I needed advertising to survive.

How did he did you find and select the writers - Robert Elms, Dylan Jones and Jon Savage?

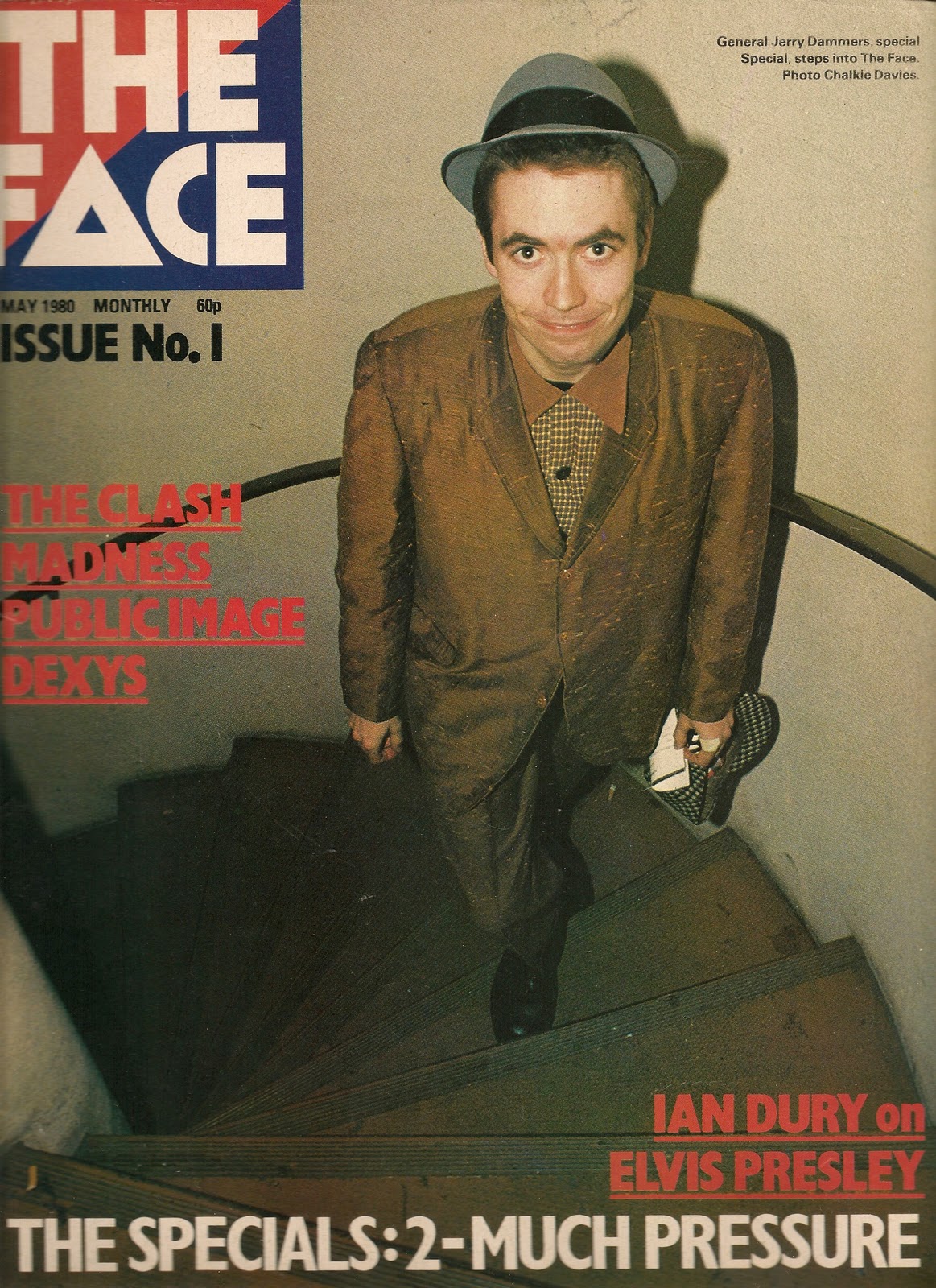

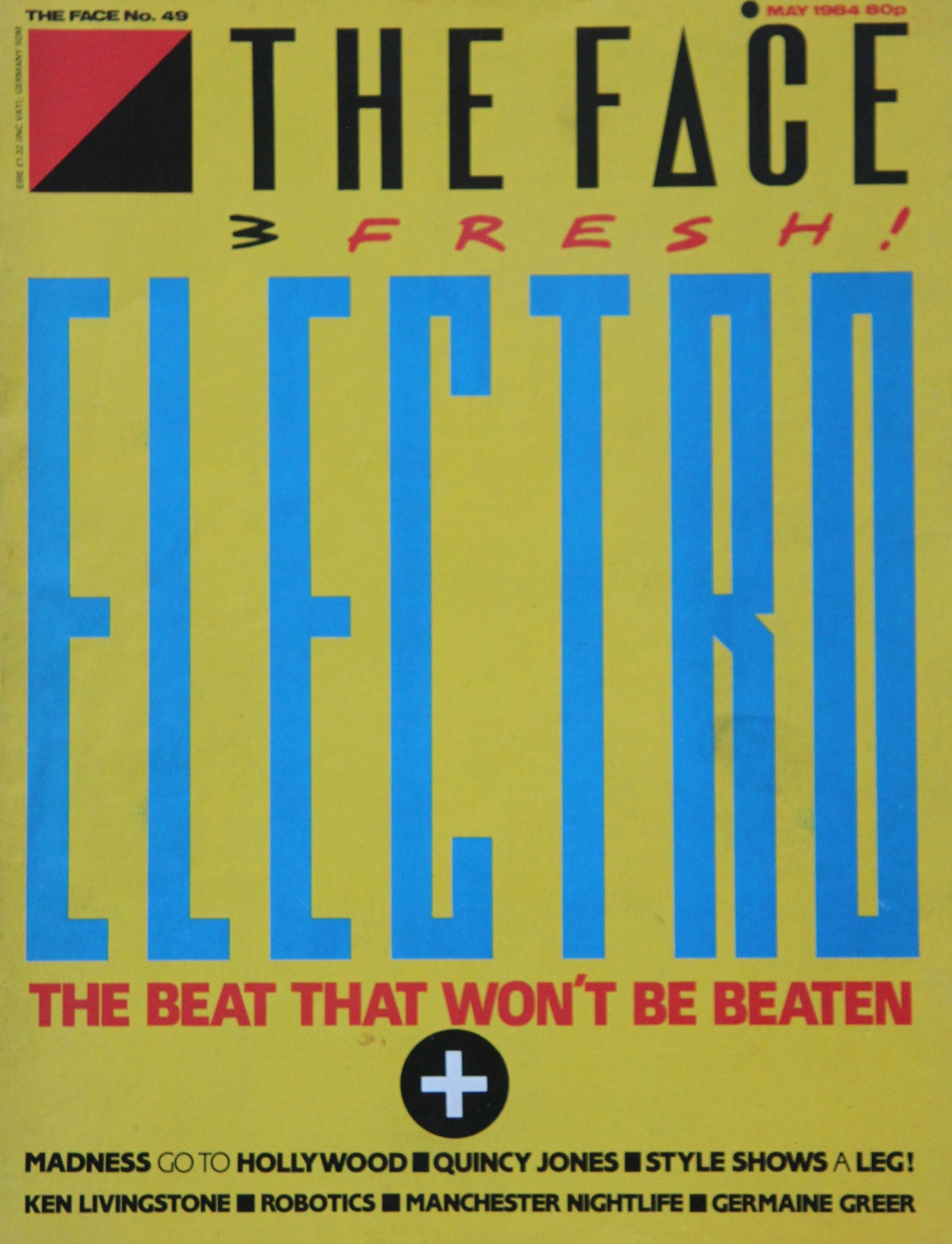

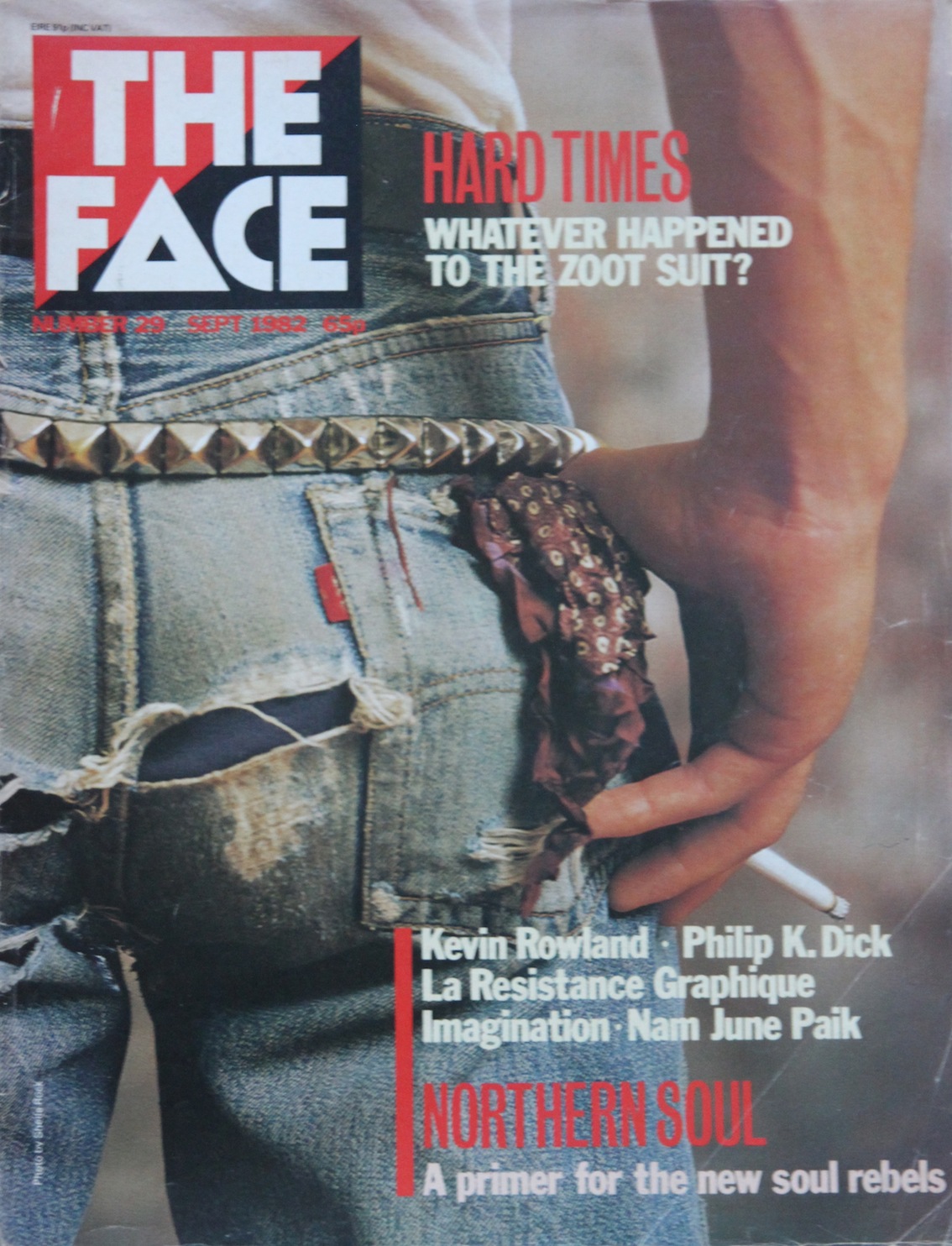

That was tough, getting writers at the beginning. Fortunately it was always going to be equally balanced between photography and writing, and there was no problem sourcing photography. The first issue of The Face had six full-page portraits and that was perfect because the writers I would have wanted were at the NME and I knew it wouldn’t go down well if I approached them to freelance for The Face. (Should mention that at this point I was the only full-time member of staff; all contributors were freelancers). It was only natural NME might be wary of what I was cooking up across the road.. I did use Adrian Thrills from NME - he did the Specials cover story in Issue One - and once I’d got Adrian I decided it would be politic not to push my luck any further with NME. Instead I found people who had written for Smash Hits. I also had the idea that I could turn non-writers into writers. I wanted a little bit of a fanzine feel, a rawness. . So Neville Brody (his classic Electro cover is above - Ed) was in Issue One but as a writer. It wasn’t a great success. And Vaughn Toulouse and Gary Crowley - who were mates, both of them wrote pieces, and again they needed a lot of editing, but that mixed approach got me through the first year of The Face.

I suppose you’re looking for the passion and understanding the subject most importantly...

Yeah. When I think back, it was unrealistic idea to have something that on one hand had the print qualities of Tatler and aspired to the reportage values of Paris Match – i.e. The Specials shot in black and white on the beach in the first issue was Paris Match-inspired - and to combine that with elements of Sniffing Glue. That was a pretty preposterous idea, but no-one was telling me what to do. I could just do whatever I wanted. And I did.

So ‘style’ was pretty important from the off?

It was to me yeah, but it wasn’t really explicit until Chalkie Davies and Sheila Rock started to give me photos that were fashion-y and posed, and then I had a bit of a dilemma about how to use them. ‘Do I want to run these?’ Yes but what’s the justification and context? You know, do they need accompanying text? So they ran, with flimsy context, and that encouraged more contributions. I had to work out how to deal with it. You have to remember there was no template at the time for a magazine like The Face. If I’d called it our Fashion Section we’d have been laughed at. Sheila might give me material for three pages, say, and others one/two pics and I’d put those together but then it was a case of ‘what to call it?’. I didn’t want use the word ‘Fashion’ so I looked for a term that didn’t play to people’s prejudices and ‘Style’ seemed like an innocuous choice for this mixed bag of fashion-lite shots.

To jump forward to when I launched Arena, again there was nothing really to base it on (Ed: this was pre-GQ and Esquire UK editions). There was US Esquire, which had great, grown-up features but also a distinctly American ‘voice’. There was no equivalent ‘voice’ for a British men’s magazine because the category didn’t exist, there was no context or existing framework. Not a problem with the general features and interviews but when it came to the fashion coverage and stuff like haircuts, blow jobs, grooming …those kind of subjects … you have to experiment and see what works, to get the balance right, all those subleties. It may seem easy now but it wasn’t at the time.

I think that’s the beauty of it and as you see the magazine develop you can see that...

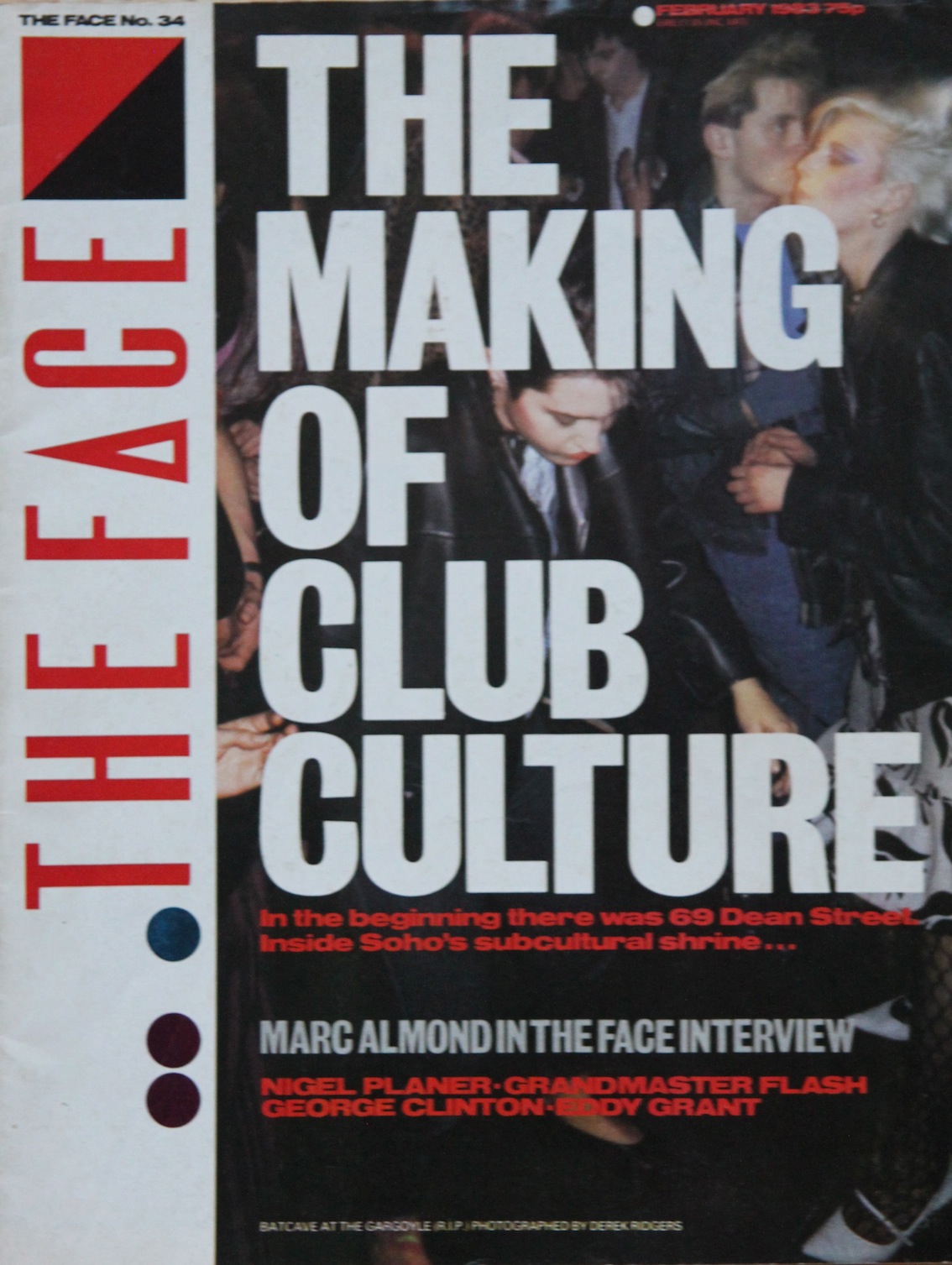

We were making it up as we went along on The Face. I don’t think we started nailing it until around ’83. Sales started well and then began to fall away, which is the normal pattern. You launch and then lose say thirty percent, then another ten percent. Finally sales stabilise and climb to a level ahead of where you started. But mine went down, stayed down, and I was desperately worried. What do I do? What does it take? And I couldn’t find the answer. But two things definitely moved us forward. One, when Robert Elms came by after the NME showed him the door. He wanted to write about the burgeoning Club Culture and his friends Spandau Ballet. I could easily relate to clubbing culture if not immediately to the participants. Better still, the NME is ignoring it, it’s highly photogenic, and I have a young enthusiastic writer.

Then there was Neville Brody. I came across him when Smash Hits was looking for an Art Director. He was fantastic, very talented, but too ‘punk’ for Smash Hits. I thought I’d keep in touch with him and, jumping some 18 months, we end up sharing office/studio space, him doing his freelance design for books and record companies, me editing The Face, by then with a staff of three. Watching us work, Neville wanted to contribute to the magazine, did a few pages and then covers and that was a huge jump forward. Previously, I’d been doing most of it myself.

Down to laying out the covers?

Oh yeah. But I’d done covers of the NME previously. I’ve always done lay-out, even on my local paper pre-NME. On The Face the first few covers and the logo were designed by Steve Bush, Art Director of Smash Hits. I had started The Face from the Smash Hits offices, did that for about ten months and then moved out and worked with Dave Fudger, ex-Sounds, but Dave’s layout style, so good on Sounds, didn’t really adapt, so Dave did a few covers and I did most of them after that. I was a bit peeved when I was the V&A Post Modernism exhibition and they’ve got these little notebooks etc in the gift shop with covers on them, all credited to Neville (laughs) though two of them were mine, and I didn’t even get an invite to the opening of the exhibition.

The thing I loved at the time was 2-Tone. I thought the music was fantastic but it was also so photogenic. It had a monochrome image but I knew it would work in colour too.

So that’s why Jerry Dammers is such a feature of the early magazines?

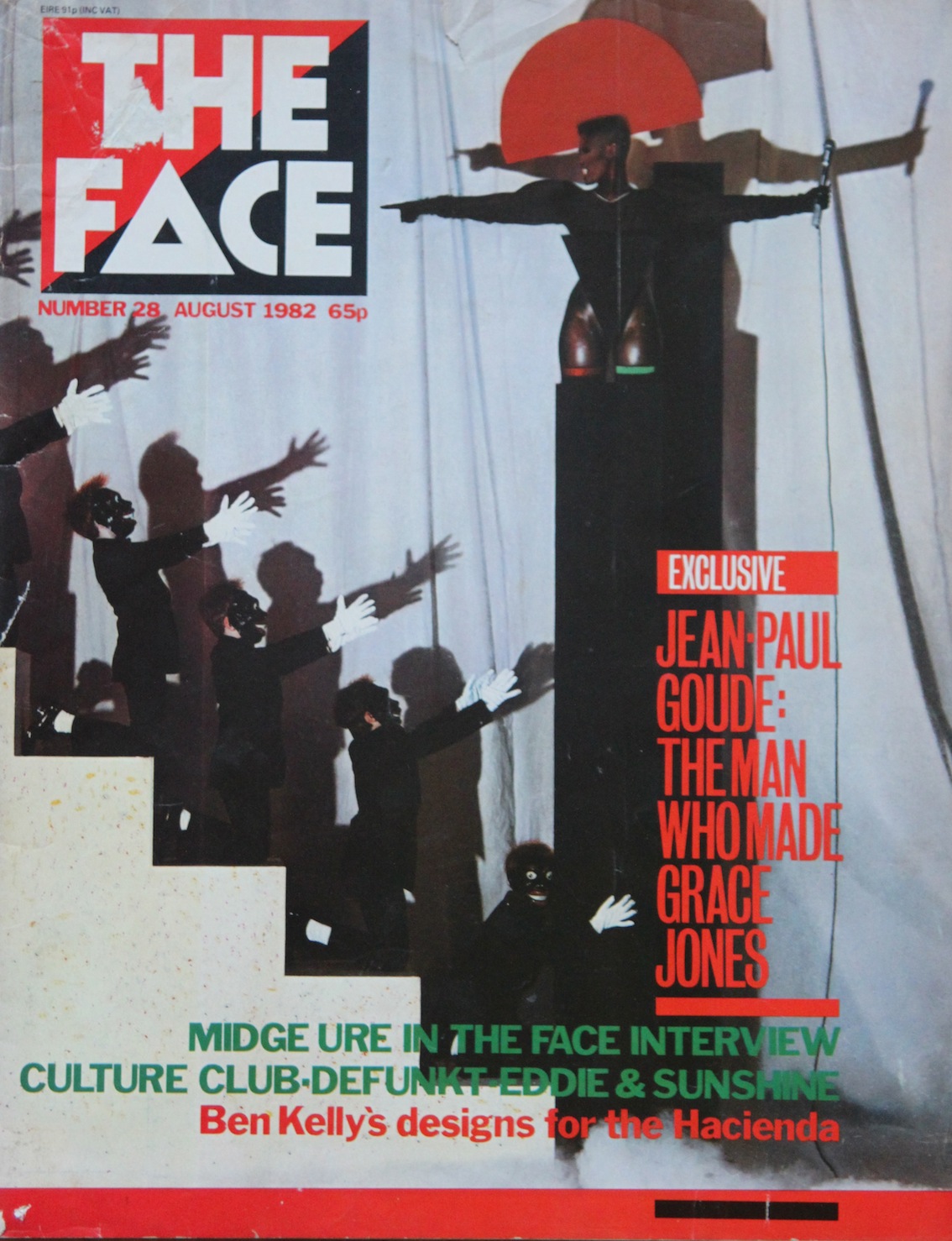

I did the program notes for an exhibition on Lloyd Johnson recently and I wrote that Lloyd Johnson (style legend and boutique owner) was the first or second name on my features list, as his shop embodied music and fashion and lent itself to that Paris Match-style reportage over six pages and was absolutely spot-on for conveying the editorial message such as it was. And the other one at the top of the list was 2-Tone, and even though it wasn’t particularly a new phenomenon by that time, I still wanted it to be in there because it was so photogenic and I felt like I owed the music a debt for the inspiration it gave me, and I loved Jerry Dammers and The Specials, but of course it was on a slow decline by then, and the next thing that came along was Club Culture and the New Romantics.

It had a very ‘club’ focus from early on. Were you heavily involved in the scene at that point?

I love music. Still get moved by it. There was a period when I was at Smash Hits when I could tell you every record in the Top 100. I would be familiar with them because I had to be and wanted to be. And the same at the NME, but I have probably always been a few years too old, in my mind, to be part of any scene. Like with punk, I was 28 at the time, but the music was for 18/19 year olds. It didn’t stop me going to see The Ramones at the Astoria but it did stop me going to The Roxy (Don Letts famous punk club soundtracked by his love of reggae). Similarly I didn’t hang out at The Blitz or Beat Route, though there is a picture of me somewhere with Chris Sullivan at The Wag.

The Wag had more of a Soho slant to it I guess... What were the clubs you grew up with?

One of my abiding memories is of the Tottenham Royal. You know anything about that? It was a big Mecca dancehall in north London and it was the absolute peak, for me, of the soul and Mod movement. It was ‘the’ place to be in the 60s. Maybe ’64 to ’68/’69. It was an amazing scene. There was also the Ilford Palais but that was rubbish in comparison and the Streatham Locarno which was south of the river so that was shit (laughs). The Royal was immense. All the best music going on and it was a Mod scene and it meant so much to me. People came from all over east and north London, from Hackney, Shoreditch, Muswell Hill, Crouch End, rough guys some of them, and there were occasionally fights outside, but as long as you were reasonable it was a really great scene… A fantastic sense of community and camaraderie, and all that amazing music pouring in from the USA. Ask any Mod of the time in north London and they’ll tell you that was the place. Slightly less so The Wag and the Chez Don in Hackney. That was my thing. So when I was editing the magazines, married with a couple of kids, I’d go to gigs but I wasn’t going to hang around the back of a someone else’s club.

So moving through The Face timeline from Brody and Elms when did you first meet Ray Petri and when did you first appreciate how great he was?

Jamie Morgan, the photographer, introduced Ray to the magazine. Probably around ’83/’84.

When you find someone with that talent like him or Brody did you always give them carte blanche to do what they wanted as Petri clearly had a lot of freedom to do what he wanted within the magazine?

I think the answer is yes. At this stage there was probably four/five staff, including myself, and our editorial brief was fluid and open. I had no one to answer to. I’d commission pieces about things that maybe I’d seen driving in to work, stuff that was in my head, and provided others didn’t say ‘that’s ridiculous’ we’d cover it. It wasn’t PR-driven. Someone else might be enthusiastic about Memphis Furniture or Italian Style, I’d think yeah that’s great and it’s photogenic. I have never been an editor who imposed his ego, though difficult for me to say that about myself. It was like a tiny staff and a growing band of contributors who could come in and pitch ideas.

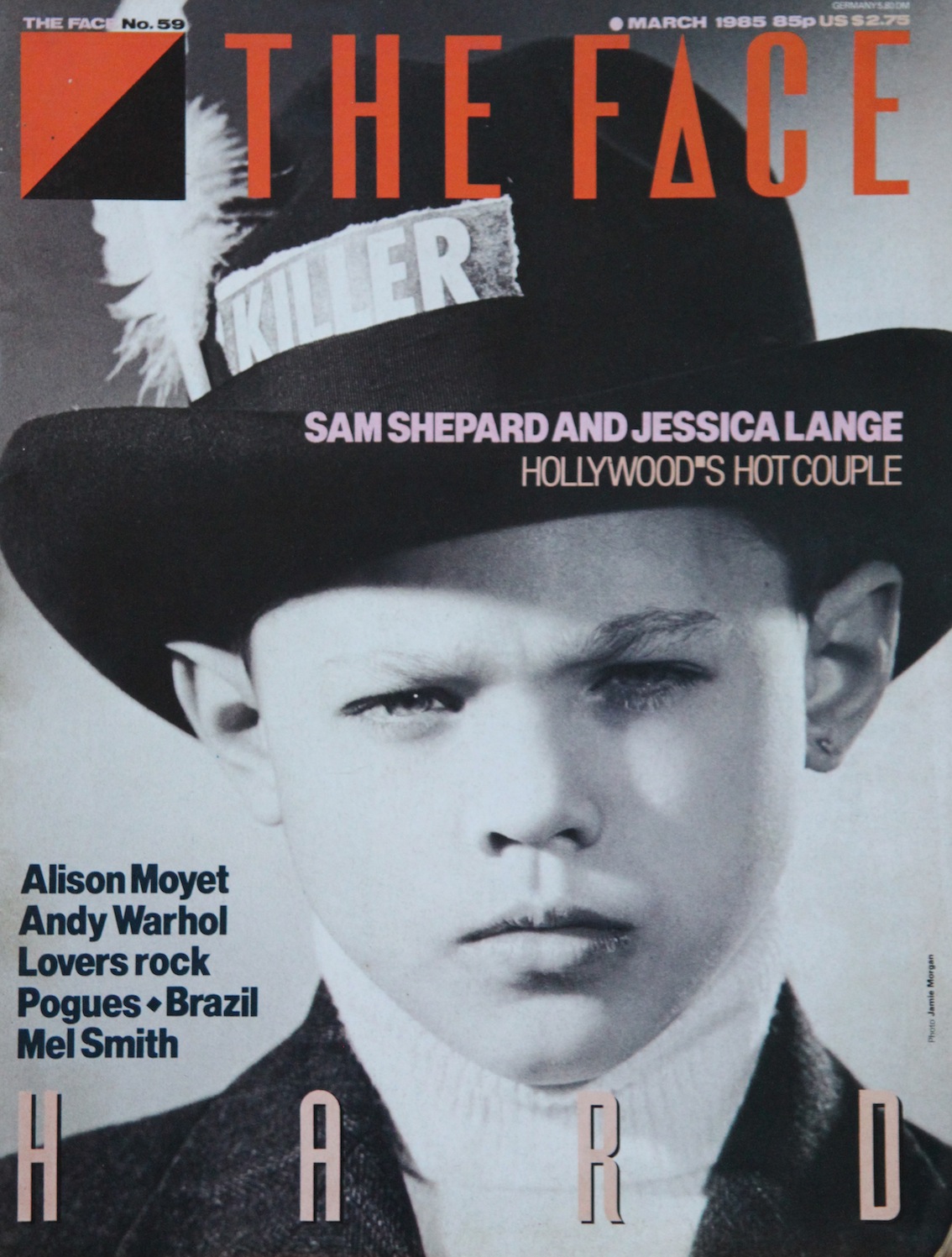

The one factor I had to keep in mind that others didn’t was the commerciality, as our existence depended on it. (Looking at the famous Petri ‘Killer’ cover with Felix on it). You know, when the pictures came in for that shoot I thought they were absolutely fantastic and there was a lobby from Jamie and Ray in support of the Felix image as a cover. I looked at it and I thought ‘it’s a 14 year old kid, what does that say about us?’ I wasn’t sure we were established enough. You could do that five years down the line maybe, but in the end, as I’ve usually done, I went with it and of course it was the right thing to do. At the time I was concerned that it wouldn’t be commercial but you look back now and it’s iconic but at the time I was worried people would say ‘what the fuck is this?’. So it was very open in the magazine. Almost anybody could come in and say they really liked something and we’d do it as long as it wasn’t ridiculous. I was a big Walter Matthau fan and the only reason there is a profile of him in issue one of Arena is because I liked him and that’s the only reason it’s there. No commercial justification at all.

So you became ill. Was that the deciding factor in giving up the Editorship of the magazine or was it an awareness the running two titles was too much? Who came after you as Editor at The Face? Was it Sheryl Garratt?

Yeah it was really. I was editing both Arena and The Face. I was off for nine months and then came back to that awful Jason Donovan period (Donovan famously sued The Face for 'outing' him - Ed). I could go on about that for a long time but there’s no point. It was a very tough, awful time. There was Kate Flett and Sheryl together covering when I was ill though I was probably still listed as editor, then Sheryl was the first proper editor, then Richard Benson, Adam Higginbotham and Johnny Davis.

I quite like the idea that editors of The Face have never quite been what people might expect. Very early on we went to New York to do a Face night at Danceteria. The Americans were a bit surprised that I wasn’t Steve Strange. I was wearing a Paul Smith Prince of Wales check suit and a black Fred Perry and there were locals turning up dressed like that month’s Ray Petri shoot. I’m a journalist (or was), I came from newspapers and the NME as a journalist, and that’s what drove me. I didn’t care what people looked like if they could do the job.

In the Johnny Davis era you had to pulp a whole run of your Eminem issue because the Art Director changed the colour of his Lacoste top from blue to pink. What kind of back from print disasters do you remember?

If it happened that must have been during the EMAP period. We’d have gone bust if I had to pulp an issue.

The Face and i-D were good examples of a time when you had creative editors, not corporate editors. Where do you find this now? Is this one of the main reasons that publishing has perhaps lost its impact and in turn voice?

We were independent and I wasn’t answerable to anybody and that’s the situation I had manouvred myself into, as I was never confident in dealing with corporations. I never liked giving speeches and stuff. If you’re trying to do things by committee that’s not a situation I can operate in. I’ll just back away. On my own I can follow my instincts and luckily for me my instincts have served me very well.

When the Face was still Wagadon published and pre-EMAP writers have told me that they never had anything to do with the advertising or marketing people. They didn’t even know what they looked like. Was this a conscious decision on your part? Did you think that they should be kept totally separate?

Well they could have just walked over to the other side of the office (laughs). So I’m surprised they say that. One of things I used to take pleasure in at Wagadon was people mixing between the magazines and departments. Staff socializing together, cross titles/departments… That was the kind of company that I wanted. Definitely no segregation, quite the opposite.

How did you see the readership of The Face initially?

I didn’t have much of a clue. I would clutch on any bit of feedback. But I realised in later years that the likes of Dylan Jones and Kate Flett had bought the first issue, and that was great to hear and I still do hear it from people. It was very lonely for the first year as I was the only person doing it and dealing with the financial implications. With the NME, and I tried to do the same at Smash Hits and The Face, I was reaching out to people and trying to create a network, a community. It’s funny, apparently when Julie Burchill and Tony Parsons got their jobs at the NME, Nick Hornby also applied for the job so you suddenly realise that these were the people out there buying it. I had no idea but I was trying to create that sense of belonging to something, which is what I wanted when I was 15/16 stuck out in Lincoln. In any community there is maybe a little group who are into their clothes and music, and out of those, say, ten people there are probably only one or two that buy magazines and maybe one that might buy one regularly.

In comparison to i-D, which you could say was talking to a smaller London-based demographic, The Face always felt like it was reaching out further to Glasgow, Liverpool, New York...

That’s what I wanted to do. I don’t want to knock i-D as I have the hugest respect for them but that was the goal. To get national and international distribution and reach out as much as possible.

To reach a mass of people is hard to do. It’s always easy to do the cool thing. How did you get tired of the business?

Well increasingly publishers were giving away free things with magazines. Cover-mounted CDs - you know. What are you buying, a record or a magazine? They were so desperate to stop magazine sales declining whereas something like The Face, or i-D or Dazed, should be able to look and say that’s the core and it’s never going to be huge and if that drops by ten percent it’s probably because of the demographic but if it drops off by fifty percent there is probably something wrong with the magazine. If people could accept that, it could allow magazines to grow and develop organically but some of the men’s magazines would be doing anything to keep readership and to stop circulations declining. But why can’t it go down? It doesn’t necessarily mean a publication has lost the plot. Maybe the demographic has changed. That’s acceptable, the magazine is still good. You can become a slave to chasing those figures.

Once you sold The Face to EMAP how did you feel watching your magazine change and not being able to do anything about it?

It would have been different if I had been editor at the time but I wasn’t – I’d long ago pulled back into the role of editorial director overseeing 4/5 titles. Plus I’ve always tried to move on when things finish; it wasn’t as difficult as I thought it might be. First emotion was the tremendous release of pressure... I’d been a journalist since the age of 16 and working at a pretty grueling pace for 20-25 years. The reasons I sold up? It’s complex : there were many, many reasons, and if I was to detail them all we’d be here for another couple of hours. Let’s just say that I just felt that I’d had enough of the responsibilities that come with different titles and some 70 staff, and I didn’t have anything else to prove, to myself or anyone else.

What are you doing now?

I’m working on projects. I’ve invested in a small hotel in the Eastern Algarve that my daughter and her family will run – that’s due to open in the summer. There are also a couple of publishing projects: a writer who wants me to cooperate on a book about my time at NME and another who I’ll work with on a book about The Face.

Thanks for your time Nick.

Thank you.

© Nick Logan 2012

If you want to read some our favourite Face articles from over the years then click here.