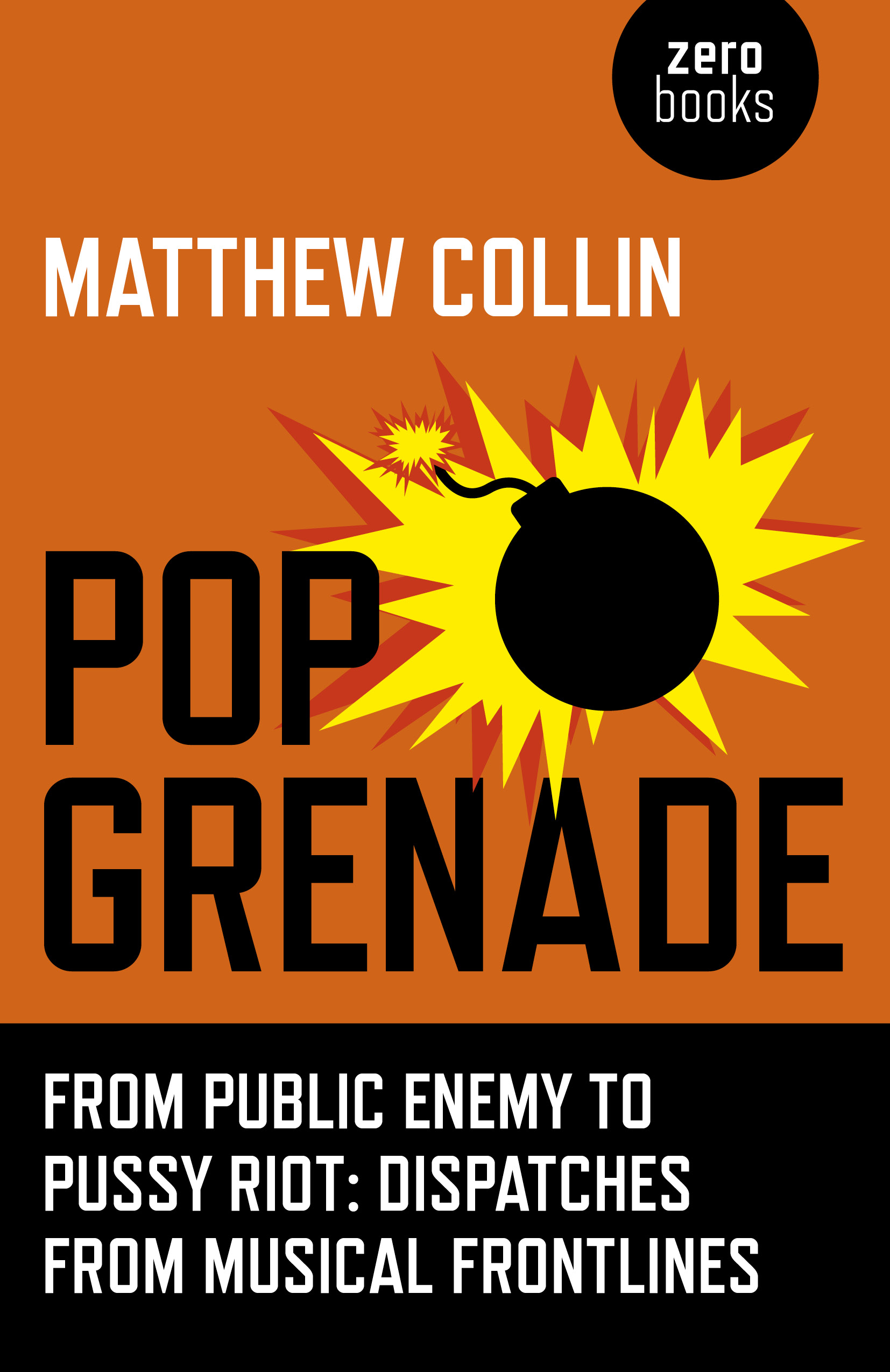

Matthew Collin

Public Enemy Launch A Pop Grenade

Extract

In an extract from his new book 'Pop Grenade: From Public Enemy to Pussy Riot - Dispatches from Musical Frontlines’, author Matthew Collin recalls the seismic impact of Public Enemy’s afro-futurist hip-hop in the late eighties.

It’s hard to remember now, so long afterwards, just how Public Enemy dropped like a sonic cluster-bomb into the collective consciousness of British youth back in 1987 when they first toured the country - an experience that was to be as life-changing for them as it was for us.

For many of us who rushed to buy the first Public Enemy records, they seemed to represent a fulfillment of the desire for genuinely progressive pop. Along with Mantronix, KRS-One, Run-DMC, the Beastie Boys and Eric B. & Rakim, here, it seemed, was music worth believing in again - a sound, at last, that made us feel truly alive.

The anticipation had been rising steadily since their first British release, Public Enemy No. 1, in 1987. Most of us had still only read about the band in the music papers: the ‘Black Panthers of rap’, the new militants of the hip-hop age, incandescent with revolutionary zeal, come to blast our brains apart with the kind of electronic assault we didn’t even have the strength of imagination to dream about. I remember getting my copy back from the record shop one evening: the matt-black sleeve, the iconic Def Jam Records logo - the definition of where it’s at, at that time - and putting the needle to the groove for the first time… and then this unimaginable dervish howl, this frantic eruption of squalling frequencies that I would only later discover was sampled from Fred Wesley and the JBs’ Blow Your Head… and indeed, my head was blown; a few short minutes later, nothing could be the same again.

When Public Enemy arrived in Britain in 1987, they were already into an incredible run of hits that would redefine the possibilities of what both hip-hop and rock music could hope to be. This was sonic futurism - Afro-futurism, to be more precise - in full and total effect. Not just ‘bass for your face’, although there was plenty enough of that too, but something much more ambitious.

Hip-hop had always been intrinsically avant-garde music, from the funky bricolage of Grandmaster Flash’s Adventures on the Wheels of Steel to the chilly Kraftwerk textures and cosmic reveries of Afrika Bambaataa’s Planet Rock, with its utopian narrative of a world without earthly cares, “where nature’s children dance inside a trance”.

Exploring how early sampling technology could twist snippets of sound into previously unimaginable new forms, Public Enemy’s production team, the Bomb Squad - Hank and Keith Shocklee, Eric ‘Vietnam’ Sadler and rapper Chuck D himself under the alias of ‘Carl Ryder’ - took this idea of irreverent recontextualisation right beyond the frontiers, setting out to be as revolutionary in sonic terms as they were in their lyrics.

“Hank [Shocklee] and Chuck didn’t want music. They wanted non-music, aggravation, noise,” Sadler told me more than two decades later. “They would do things that made absolutely no sense at all musically, but they were funky. Studio engineers kept telling us, ‘you can’t do this, you can’t do that’. But I learned that there are no rules, you can do whatever you want.”

Beats were overdubbed and overdubbed again until they were unrecognisable, loops of tape were stretched around studios to elongate grooves, samples were processed and re-sampled until they degenerated into grungey static, or re-layered over and over, until another, previously unimaginable sound emerged.

“We had to push the equipment to its limits because at the time, when we started, there was so little equipment available, and we had to invent new ways of doing things,” Hank Shocklee explained. “This is where the hip-hop concept of the turntable being an instrument comes from - we used the turntable not as a record player but as a sound-design tool.” Sounds were seized from all over Shocklee’s huge library of discs: from Funkadelic, the Temptations, Isaac Hayes and other soul giants to metalheads Anthrax and even British glam-rockers The Sweet.

The music was intended to sound like an alarm call. “We were trying to make people think, ‘What the fuck is this?’” said Chuck D. “There was nothing ‘appealing’ about any of our music - it was jarring. We were trying to beat people over the head, to make them take notice.”

It also had to embody the urgency of the moment: New York City in the dread late eighties era of racist vigilantes, crack zombies and blood-lusting cops. “It was speaking for the underdog, the underclass, the have-nots. So it couldn’t be melodic. It had to be atonal, to provoke a reaction with sound,” Shocklee said.

The Bomb Squad tried to harness the raw power of rock’n’roll, the spirit of Jimi Hendrix as well as James Brown, to give the beats more aggression. “At the time when PE came out, nobody gave a shit about anything. People were lost, they didn’t have any direction,” Shocklee recalled. “PE came in and said: ‘No! We need to be talking about what is going on, we need to wake everybody up, get everybody out of their trance.’ So it had to be abrasive, it had to be loud, and it had to say things that no one would say but needed to be heard out there.”

They sought to drench Chuck’s stentorian declamations in a roiling torrent of panicked energy. “Chuck’s natural vocal is a baritone, he has a voice almost like a Baptist minister. If you put music around him that’s melodic, the message and the energy will get lost because it will all blend in together,” Shocklee explained.

“So the only way is to create a thunderstorm of sound so that he doesn’t come across like a Baptist minister, but like the voice of God - a voice that resonates with fire and brimstone. The music had to be like lightning bolts coming from heaven, like hail-storms and tornados.”

After the squalling racket of Public Enemy No. 1 and the wrecking-ball beats of their debut album, Yo! Bum Rush the Show, Public Enemy fired off a series of singles that remains unparalleled in hip-hop: Rebel Without a Pause, then Bring the Noise and Don’t Believe the Hype, and the following year their best-known song, Fight the Power.

Inspired by the clarion call from the Isley Brothers’ driving seventies funk groove - “you got to fight the powers that be!” - Fight the Power was commissioned by rising black film-maker Spike Lee for the soundtrack of his 1989 film Do the Right Thing, a drama about the tempestuous racial relations between New York’s African-Americans and Italians, set amid a broiling Brooklyn summer. “When this film came out, some people said it was going to cause riots all across America,” Lee said later. He had originally wanted to open the movie with a contemporary version of the ‘black national anthem’, Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing. The cherished old classic spoke of the “harmonies of liberty”, but what Public Enemy gave Lee was a very different interpretation what that could mean.

“1989, the number, another summer,” Fight the Power begins, as Chuck D, who once said that black people “should look at the American flag like a Jewish person looks at the swastika”, used the song to take aim at two of conservative America’s pop culture icons: Elvis Presley, who he accused of stealing the souls of black musical pioneers for his own profit, and John Wayne, the right-wing actor who once said that he believed in white supremacy “until the blacks are educated to a point of responsibility”.

The song plays again and throughout Lee’s film on a beatbox carried by one of the characters, Radio Raheem - and at the climax when an angry Italian pizza-parlour owner takes a baseball bat to the young rap fan’s ghettoblaster in an act of symbolic repression intended to silence the voices of resistance.

Lee also directed the video for Public Enemy’s single release of Fight the Power. In its full, seven-minute version, PE’s clip opens with archive newsreel footage of civil-rights activists rallying in Washington in 1963, carrying placards demanding an “end to bias” and singing We Will Overcome as they gather to hear to Martin Luther King speak.

It then cuts to another rally, this time in full colour, with Chuck D addressing a teeming street full of demonstrators who are holding placards of Malcolm X, activist Angela Davis, boxer Muhammad Ali and the PE crew. “Yeah, check this out man, we rolling this way. That march in 1963, that was a bit of nonsense, we ain’t rolling that way anymore!” Chuck declaims.

Flanked by the S1Ws in black fatigues and dark shades alongside various bow-tie-wearing members of the black Muslims’ Fruit of Islam security detail, Chuck, Flavor Flav, Professor Griff and Terminator X make their way to the stage through the cheering crowd that was assembled by Lee in Brooklyn to create a tableau that portrayed PE as the political oracles of a new and very different Black Power generation, with the gospel tones of the civil-rights marchers replaced by the insurgent rhythms of hip-hop.

Indeed, this was the blueprint right from the start, explained Bill Stephney, who shaped the concept of Public Enemy with Chuck D and Hank Shocklee, then went on to work for Def Jam.

“We wanted to create something that was unique, a sort of mash-up of The Clash and Run-DMC, and that’s what Public Enemy became,” Stephney told me. New York at the time was like a “racial crucible”, he recalled; a city on the edge. “The times dictated that musicians should carry on the legacy of urgent statement art, of agit-pop. We felt that in hip-hop, with the exception of The Message by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, there wasn’t any group that reflected the times. We listened to Sandinista! by The Clash and said, why can’t we do that?”

Just as The Clash once did, Public Enemy tried to bring radical ideas to a mainstream audience, while Chuck D’s lyrics were like a packed grenade: detonate it and all kinds of ideological shrapnel would burst outwards in a frantic shower of potential inspirations.

“We want poems that kill,” demanded African-American writer Amiri Baraka back in the sixties. “Assassin poems, poems that shoot guns.”

Now here they were.

‘Pop Grenade: From Public Enemy to Pussy Riot - Dispatches from Musical Frontlines’ by Matthew Collin is published by Zero Books. More info here.