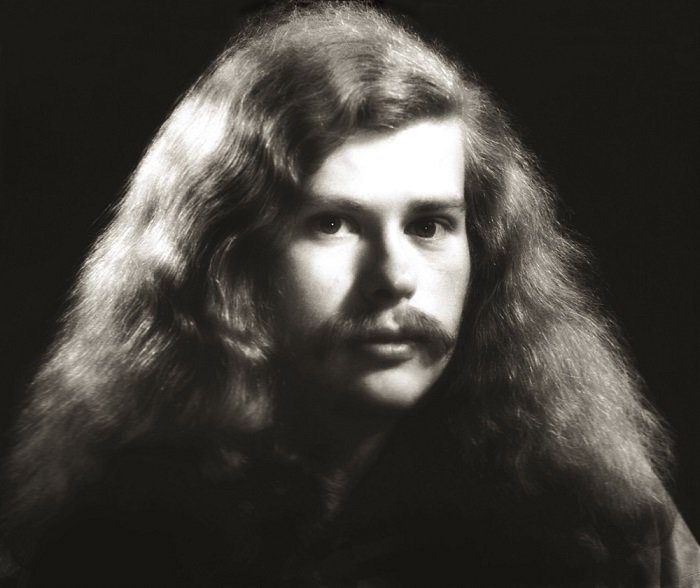

In the nineteen-seventies, Danish keyboardist and producer Klaus Schønning was living in Copenhagen, touring throughout Denmark and Germany, and building a rudimentary home studio. As jazz, rock and punk music exploded throughout Denmark, Schønning strayed off their well-worn paths. “I started playing the piano and getting classical piano lessons in the middle of the sixties,” he recalls. “When I left school, I got a little electric organ, and I started to play together with some schoolmates in a little band. I got very interested in keyboards, purchased a tape recorder and started to make recordings.”

The psychedelic rock sounds of The Doors and Pink Floyd were the soundtrack of the era in Denmark. Schønning had an affinity for some of their more experimental impulses, but he was far more captivated by classical - in particular, Wendy Douglas’ Moog renditions of Bach - and folkloric music from across the globe. Understandably - if you’ve heard “Switched-On Bach” - those early keyboards and tape recorder purchases were opening up stargates in his mind. “I just saw the many possibilities that were there with the tape recorder and the keyboard. The keyboard with more sounds, and the tape recorder with more tracks,” Schønning says. “I said to myself, 'Well, I am now able to play with myself!' I started to make music where I play all the voices and all the tunes.”

On Lydglimt: If you listen to my first album, you can hear that I’ve added some nature sounds from the woods, and then from the beach, the water, the wind in the trees and all that, which I also think was fundamental.

That technology - primitive by today’s standards - allowed Schønning to realise his sound. Within that frame, his primary influences were two-part: The unique textualities afforded by keyboards and synthesizers; and the compositional possibilities of multi-track recording. Interestingly, although was making these discoveries in parallel with the emergence of European and Japanese New Age and Kosmische acts such as Jean-Michel Jarre, Tangerine Dream and Kitarō, Schønning was unaware of their work at the time.

The final piece in the puzzle was when he discovered he could record the sounds of nature and compose around them with his electronic tools. “If you listen to my first album, you can hear that I've added some nature sounds from the woods, and then from the beach, the water, the wind in the trees and all that, which I also think was fundamental,” Schønning explains. “I couldn't do it with the instruments, but I added some real sounds to get a flair of something basic in it. So it was not too technological; to add some humanizing expression into the music.”

That first album was “Lydglimt”, recorded at home, and privately pressed and released through Schønning’s Klaus Schønnings Lydlaboratorium label in 1979, just as New Age music was beginning to explode around the world. “I can see I had saved up a lot of ideas and a lot of motivation for doing this because I believe that it's just like a painter painting, you know, you have all the colours,” he reflects. A painter is also alone when he does his job, paints his picture. I felt more like that than I felt like a musician.”

Over thirteen tracks, Schønning mapped out a distinctive sonic topography. Lyrical synthesiser, organ, clavinet and guitar melodies expand into expansive symphonics and D.I.Y. experimentalism, all interwoven and geo-stamped by the field recordings he discussed earlier, and mood-specific song titles like ‘Lysstrejf’ (Light Beam), ‘Aftenregn’ (Evening Rain) and ‘Klittåge’ (Dune Mist). Over the decades to come, Schønning’s work on “Lydglimt” would position him as a pioneer in scenes he knew nothing about. “I didn't hear about Jean Michel Jarre’s “Oxygène” until 1982,” he says. “I didn't have anybody to compare myself with. It was a mixture of modern possibility. In the older days, I was moving ahead on a new path that nobody had walked before really.”

As the snow fell in Copenhagen in 1979, Schønning biked around the city with a box full of records to sell. The following year, he unveiled a second self-released, similarly conceptual album, “Cyclus”. “Part of my story is that people wrote about it in the newspapers, maybe because of the music, but also because of the history,” he explains. “I did it all myself, and I rode on my bicycle around the record shops and asked them to put some of the LPs in the windows. I had to do everything myself, and the record company found that was very funny. So, they made a contract with me to do another album, in a real record studio.”

Through that experience, Schønning entered the European major label world, where between 1982 and 2018, he released over twenty more solo albums as well as countless collaborative projects before going independent again. Not everyone finds their way in the system, but for Schønning, it was relatively smooth sailing.

“I didn't feel that they were trying to change what I did,” he says. “Of course, if somebody said, I think it's a bit long this part, that was fine. I'm not so stubborn that I do not listen to what people say, but what was important for me, was that I had the freedom to do it. They could feel that I had thought about what I was doing. That all said, he adds a proviso: “Without those first two albums, I don’t think I would have gotten a contract with a record label. Today, it's just like a circle; you go back to where you started.”

On Suzanne Menzel: I think she had a wonderful voice and I liked the music and the moods.

In 1981, Schønning received a letter from a thirty one year old singer-songwriter named Suzanne Menzel. Menzel came from a background in choirs, church music and live bands, but she was looking for something more from music. “Suzanne [Menzel] read about me in the newspaper,” he says. “She liked that the story was a little funny and that I could do that without a record company behind it.” In her letter, Menzel explained that she sang in English, played acoustic guitar and had written lyrics and music for an album worth of songs. “She sent me a cassette tape, I listened to it, and I liked it very much.”

Those songs became Menzel’s privately pressed “Goodbyes and Beginnings” album, one of the most unique singer-songwriter records recorded in Europe during the early nineteen-eighties. “I think she had a wonderful voice and I liked the music and the moods,” enthuses Schønning. Menzel was looking for somewhere to record, and Schønning suggested that she use his home studio and let him compose some arrangements around her songs using his rhythm-computer, synthesisers, clavinet, piano, auto-harp, and a selection of folkloric instruments and percussion tools.

“She was very open to that,” Schønning says. “There were so many singers, guitar players singing their own songs at the time, so she came to me. I listened to the songs and some of them I said, ‘Well, we should keep them just like they are, or just do a little bit, put a little bass line in,’ and others sort of called me to make more of an arrangement for them. So when we did that, it was a very good, good process because she had confidence in what I did. We got a solution where I sort of put my fingerprint on each of her songs. It did very fine, I think she was very happy with the result; and so was I.”

“Goodbyes and Beginnings” contained some remarkable songs, like Menzel’s clavinet and rhythm-computer led synth-folk number ‘I Feel It Starts Again’, which the open-eared DJ Hunee described as “The track I’d play at my funeral” in a 2015 interview with The Guardian. ‘I Feel It Starts Again’ is followed by the equally remarkable lyrical dreamscapes of ‘This Is Not My Life’, two high watermark moments on a record which, thirty nine years after its original release, still occupies a singular liminal zone.

“But again, it was in a time we couldn't do a lot with it, and we didn't sell many copies,” Schønning admits. “So it was fantastic, for me that so many years later, Andreas released the album.” When Schønning says Andreas, he’s talking about New York-based Danish video journalist Andreas Vingaard, who in 2016, reissued “Goodbyes and Beginnings” through his boutique Frederiksberg Records label. Unfortunately, it was fifteen years too late for Menzel, who died of cancer in 2001. “It was a pity,” Schønning says. “I hadn’t had contact with her for many years and she never got to experience the new success with the album.”

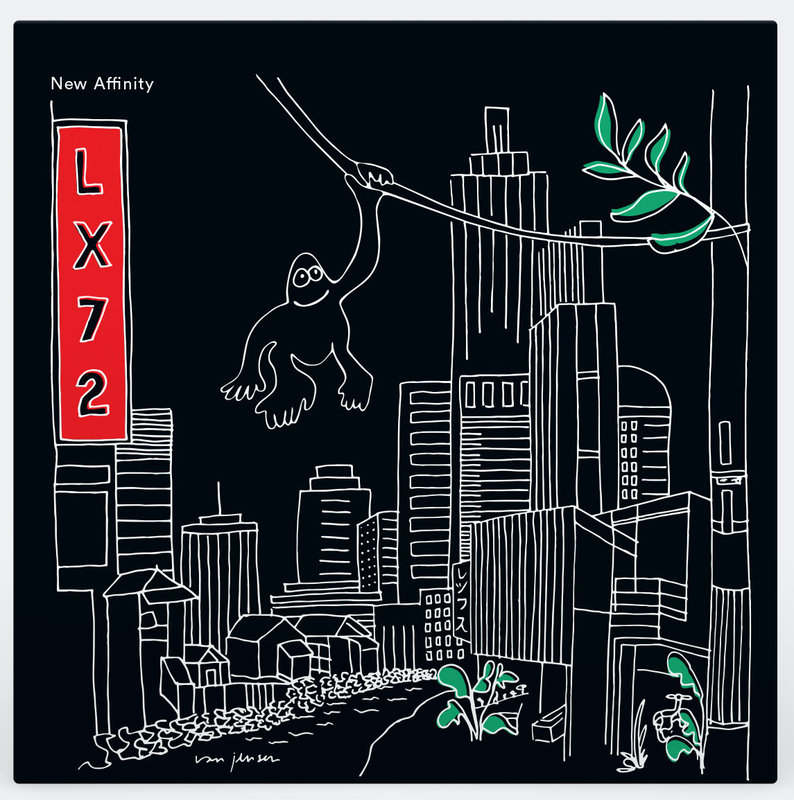

In the midst of that sadness, Schønning forged a connection with Vingaard, who arranged to reissue “Lydglimt” to celebrate the cult album’s 40th anniversary. “We’d originally planned to re-release it in 2019, but it was a bit delayed with test pressings, pressing plants, and everything else going on,” Schønning explains. “What can you do, does it even matter?”

“Lydglimt” is out now through Frederiksberg Records in LP and digital formats (order here)