SUMMARY KEYWORDS

people, bit, ai, big, called, album, nice, early, music, pretty, years, work, released, chip, presets, sound, write, record, happen, weird

SPEAKERS

Paul Test Pressing, Matthew ALM Busy Circuits, Ed Handley (Plaid) & Andy Turner (Plaid)

An Introduction…

I like Plaid. A lot. Always have since I was young. I’m also a massive fan of the music they made alongside Ken Downie as Black Dog. Around my early twenties I worked at their then record label General Productions for a while. It was a chaotic place but the label released so much good music (Luke Slater’s 7th Plain etc).

This interview moves from a look into Black Dog Productions and the early days of Plaid then on to a conversation about AI which has been an influence on Plaid’s new album ‘Feorm Falorx’. The new album is far more fun than you might expect if you know their work. It has their trademark melodies and keeps the rhythms to the fore but leans into Italo Disco and other fun elements you might not consider as part of their orbit.

The album’s artwork were created using a myriad of AI technology, Image Synthesis and OpenAI's DALL·E. As keen advocates of technology fittingly I sent the recording of this interview via networks to a friend who then had it transcribed via AI and sent it back in a document.

A good friend Matthew Allum is also a fan of Plaid / Black Dog Productions so off we went to North London to meet the duo. We join this interview midway through Matthew of ALM Busy Circuits (modular synthesists of note) talking about ‘Bytes’ by Black Dog.

Matthew: It was so different to everything else and you didn't really know too much about it or where it had come from. As a collection it was it was sort of very much sort of ahead of its time. And I think even now it's still like pretty amazing. Have you listened to it recently?

Ed: I had to listen to it again recently. Quite a lot. And I haven't listened to it for years and years. It's not bad. Obviously the mixes of the tracks are not up front but there is a lot of nice texture in there.

Paul: How did it feel when you heard it?

Ed: Lots of strange things came flooding back from from the 90s, because I hadn't really listened to in full since since then so it was pretty weird. Quite sort of emotional, but also like that thing where you smell something and you get this really intense memory. I remember all of the things that were happening around that time. It was pretty intense.

Matthew: ’Bytes’ always seemed like quite a big leap on from the Black Dog Productions releases. Like the BDP records are really sort of loopy you know. They’re still really good but then ‘Bytes’ is suddenly a massive leap in terms of production and technique.

Ed: It’s credit to Rob Mitchell from Warp Records in many ways as when we were signed he came around to our studio and was like, ‘oh my god, your monitors are shit’ and bought us some really nice Genelec monitors. Then we got a desk and also this very early digital workstation called a DD1000 which was basically like a tape. It had this huge floppy disc and a kind of scroll wheel which you can hear being used quite a lot on ‘Spanners’ where it's kind of like, a spinning wheel and it’s slowing sounds down.

Andy: It was made by Akai. It was really huge and probably had about half a gigabyte of storage or something. That was pretty good. At the time. It was pretty high end. They also do like early digital audio editing.

Paul: ‘Bytes’ sort of manages to have that pirate radio feel for me. Like it’s transmitting out of a tower block somewhere in East London. Sort of dusty and sending out these weird signals but it’s still got a roughness…

Ed: It was Ken's magical little studio and we would just spend all our waking hours in a pretty hazy time.

Paul: A smoky haze?

Ed: Yeah, but also just hazy generally. There was also this intensive learning about music and other stuff so thats what you're hearing. We were both working and we had jobs so we would just go there in the evenings and then get up and show up to work. “You sure you are capable of work today?.” “Yes.” (laughs).

Matthew: I saw this Amiga demo that I've never seen before. And it was like really early Black Dog tracks and you could tell it was Black Dog.

Andy: There was there was a quite a bit of material that never got released. We wrote quite a lot before ‘Vir2l’. I wasn't sure any of those ever came out but we made 10 cassette copies of a short album called ‘Profit’ which actually was re-released as part of ‘Trainer’.

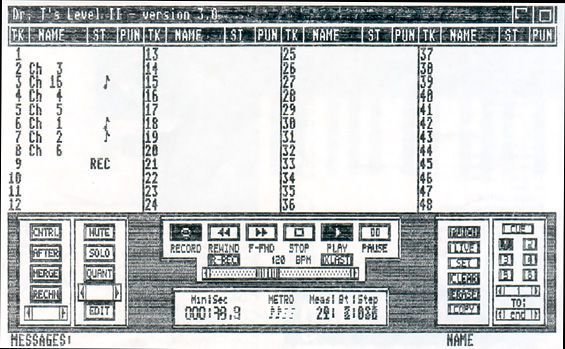

Matthew: Were you using Amiga computers to sequence using like, Dr. T's and stuff?

Andy: That Dr. T software was used. It was based on numbers. We used to use the list editor a lot. In essence we basically had the technology but we also came from a breakdancing and hip hop perspective so we loved breaks. So it was a combination of ‘this breaks amazing’ and then looping and editing. We weren't musicians really as such so we didn’t understand how music worked so we didn't do things because we wanted something different, it’s just kind of how you how it ended up.

Paul: There weren’t many people cutting the breaks like that in those early days. There was obviously things coming from different directions such as drum and bass, Dego and 4Hero and stuff I guess but that first Plaid album was really pretty technical when it came to that aspect.

Andy: I think there was a track on one of the early EP’s, and that was cutting breaks up and that was just around when jungle was kind of starting to happen. There was Blapps Posse, Shut Up & Dance going through to Aphrodite and many others. Aphrodite was really significant, chopping that ‘Amen’ break.

It’s quite amazing looking back to that period of time from ’87 to sort of early ’90 to ’92 how much technology was changing in terms of digital audio and how it influenced music and the genres that followed in the next five years.

Ed: It was suddenly possible for normal people to be able to get a little studio and start working at home and Dr. T’s was being used in conjunction with the older analog stuff whereas in the 80s the synths were so expensive so you'd have to be signed to a major record label.

Paul: I went to Aphrodite’s house around ’96 or maybe a bit later. He lived out in Bromley by where I’m from. He was still running two Atari ST’s or Amiga’s… Anyway, where's the timeline with General Productions then and Warp?

Andy: We did a few EPs on our own Black Dog Productions label then we were picked up by GPR. We did a couple of albums for them. ‘Temple of Transparent Balls’ and the ‘Parallel’ compilation.

Paul: Is it true that it was actually meant to be ‘Temple of Transparent Walls’ but you got fed up so you changed it to balls?

Ed: Yeah, I think that was kind of true. We could already start to feel things weren’t coming correct from GPR so it was our way of making a point. At the same time as that was happening we hooked up with Warp which is why ‘Bytes’ came out as a sort of compilation of various artists, because we were officially signed to GPR at that point. We did the ‘Bytes’ album as Black Dog Productions and so we had a couple of tracks on there and various other names made up for that…

Paul: You also had a Rising High release too…

Ed: Yes we did an EP for them. That was also before Warp. We also did an EP for Clear and worked with ART. We liked working with Warp and the first album went well so they signed us for more albums and importantly as artists we got paid and they accounted properly.

Andy: I don't think any of the other labels have done that. I mean, obviously GPR being the worst, but a lot of it would be like you'd be friends with them, and then put your stuff out and then that was it. They probably didn't necessarily make any money or anything but it's still nice to know where you are. So it was nice to get a statement from Warp.

Paul: How did you feel about Artificial Intelligence as a series and the way Warp sort of branded that whole sound? I mean for us as people that liked techno and wanted a sound to come down to when it was all a bit fuzzy and we’d been out all night it was literally the best music. I do remember just being like, ‘Fuck, this was what we've been looking for. My head wants to melt a bit more’.

Andy: I don't know where or who originally conceived of the idea of the Artificial Intelligence series. But yeah, I mean, they were right on the money for the moment. And they're also coming up to the 30th year anniversary of some of that stuff so represses are coming. It’s an incredible series you know.

Paul: You’ve always had a very forward thinking relationship with technology and you were very early on the internet and bulletin boards. Can you explain what a bulletin board was?

Andy: Yes. It was a series of servers set up and basically it was very, very early internet. Something Ken Downie (third Black Dog member) was was really into. We obviously realised the internet was going nowhere so we focused on music and I think we've been proven right… (laughs)

Ed: To be honest I didn't really love networking in the computing sense, and yeah, learning Linux and stuff like that. I loved music though.

Matthew: I thought you must have been coders or similar?

Ed: I was doing some database programming for a bank but no, we weren't really coders as such but we ran the bulletin boards for a few different organisations back then. And it was just ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange - character coding on the internet - Ed), it was all text based. It was starting to grow bigger and bigger. Even back then there was like an online shop I think. And so there was the first sort of online shopping and stuff.

Paul: Can you explain how it worked?

Matthew: We had it at university. What happened was someone had a modem and then there's a number and you basically dial up and type a message to the other person. I don't think much happened to be honest. That was sort of around the same time that we got email at the university and it was definitely before anyone had internet at home or anything but they had the university network and you could plug into that.

Ed: Yeah, there was pretty much no worldwideweb at that stage but then in a matter of years it just suddenly all happened. At Black Dog HQ it was kind of just there for people dialling in. You'd hear the modem clicking the box and then ‘someone's connected to our computer.’ Ken was running servers in the studio. So we've been making music and then you'd see the text and the messaging.

Paul: So it was pretty much people leaving you messages?

Andy: They were called ‘dial-in’ something or other… You'd have to have multiple lines coming into you and then you'd basically have the internet. It was really, really basic.

Matthew: It was expensive to do in the U.K as our phone lines were priced differently. In the U.S it was flat rate so it proliferated far more there. I was never allowed a modem. I really wanted to get one but my parents were like ‘No. No modem because you'll be on it all the time and running up bills’.

I remember there were all these weird ways of hacking things where you could get access by playing tones so it's like the early days of hacking and people would be trying to hack into like the missile networks. To be honest there wasn't that much to hack into because bank’s back then for example had no banking network really or if there was it was like internal networks that were very rarely on a global network. It was a kind of strange little scene.

Paul: Talking technology, my friend pointed that out the other day that using voice recognition at your bank is totally fucked now as AI is so good.

Ed: Totally. That’s over. Don’t use that. Stick to passwords and codes.

Paul: You’ve been using AI as a theme for this album right?

Andy: Well, yes. The tools have only really just become available since around April 2020 and that's really kicked everything off. I became aware of it probably in October 2020. And Emma (friend of Plaid who was busy working away in the back room) learned how to use it and so we've been having loads of fun with it. It's just insane.

You know it's coming for music next. There's already some remarkable stuff happening it just doesn’t sound that great. In maybe a year or two, you'll be able to say, ‘write me an upbeat Michael Jackson tune’, and it will. It will do that for you.

Paul: Including the voice?

Andy: Including the voice. It's pretty insane. I mean, it is troubling, but there's no way around it. So we just have to work with it. And we have to figure out ways of using it as a tool rather than as a replacement for us. But it will unfortunately replace something.

You look back at when the typewriter came in there was there was a huge uproar about that taking work away from people. It just moves from one area to another. There's always an uproar when any new technology comes in it is just this new technology is particularly disruptive. It's just moving so fast.

There's already text to video being demonstrated now. So you can literally type in what you want and it will produce a video of what you've typed. That's not commercially available, or not available to the public yet, but it's been shown in demos.

Ed: The datasets (references used to generate the work - Ed) are going to become really important. If you’re an artist and you are in that dataset how does that work? That's going to be an interesting time legally, because are they going to be paid for being in the dataset? Will there be datasets for music? And if so how does that work? Because if say OpenAI (an artificial intelligence research lab - Ed) is making loads of money by running these things, and people are paying tokens for them now, we the artists that made made the original work or reference, should probably get a slice of that.

Andy: I question if that's going to happen because it kind of comes under collaging law. You take influences from different places. I think it has been legally challenged in the States but who knows… There’s going to have to be some compensation for artists in the datasets because it is trackable. There are various legal challenges now because all the photo libraries like Shutterstock will be scraped and as they are owned by Adobe this means they are going to be in litigation. That’ll also happen with all the big film studios too when you can say ‘I want a new Marvel movie’, and then type the story that you want, and it will make it for you.

Paul: I need to play catch up a bit here but surely you need to train the machines…

Andy: The datasets are just so big and they cost a lot of money to put together. Its companies like OpenAI. They've done this. And they've really spent a fortune on it. They have so many billions of images that they're referencing and the result is what it produces is going to be original.

I mean, the most boring use for this as far as I'm concerned is to quote another artist and say, ‘I want a picture like Van Gogh's ‘Starry Night’’. The majority of people go straight for that kind of stuff. But where it interests is describing techniques, and the style you want, as there are so many ways of communicating with it that it’s going to produce really original work that's not derivative of anyone in particular. And hopefully, that's what we're trying to do.

Matthew: But can you communicate with it in a non-textual way? Because otherwise you're kind of hitting the limits of language?

Andy: There is an argument that English is slightly limited but you can pretty much describe anything you can imagine. And it will, it will try and try and achieve that for you. I mean, it's basically just like two systems, you've got CLIP (a neural network which efficiently learns visual concepts from natural language supervision - Ed) and you've got your dataset and another bit of code, and that's kind of generating what it thinks you want to see like a frog on a bike. And then it will go to CLIP ‘Hey, is this the frog on a bike?’ It will answer ‘I think 17% that's a frog on a bike’, send it back, and then you get hundreds and hundreds of back and forth until both systems go ‘Okay. 97% Sure. This is a frog on a bike’ and then it outputs it. That takes seconds.

The best one I saw was DALL-E (machine learning models developed by OpenAI to generate digital images - Ed) almost said, what is Mona Lisa’s view like? And it came with a view of a gallery from that perspective. Like how did it figure that you know? I mean, the dataset will eventually include its own productions. I'm sure that OpenAI is keeping all of the images produced via it in a database.

Ed: OpenAI is pretty cool in terms of their privacy so you are working in isolation, but with some of the other systems like Midjourney and Stability.ai all your work is open source which is kind of not how artists really work.

Andy: You want to do your practicing and development work privately rather than ‘here's my first effort and everybody can follow along’. So you have to be kind of careful which ones you use.

Paul: I guess this is just modern day sampling? A future driven version obviously…

Andy: I think AI can, and is, being used creatively. And then it can be used in un-creative kind of terrible ways as well. I mean almost all the technology we've ever built, has that possibility. Like an oscillator can be used to destroy if it's loud enough and it has been used in sonic weapons. Personally I think AI could be a brilliant assistant to us. It could really open up creativity and things that we've never even imagined. So it's kind of the best way we can look at it. And it's impossible to stop.

Ed: It will probably end up being used in a way you could never imagine like how this current internet ended up. You know the internet dream was ‘we're going to share all this information’ and it's kind of like Wikipedia ended up as what people predicted what the internet would be and the rest of the internet has ended up with things like Twitter and Instagram and Tiktok. All these kind of like weird apps that no one would have ever predicted.

Paul: You’ve always had code or algorithms influencing music be that written on a manuscript or in data. It has always been around to a point. You have musicians that write code and then edit the output into musical pieces and then the art becomes in hearing what the machines making but then taking it to make it yours, if that makes sense.

Ed: That's how we've often used generative kind of stuff. It is almost like having a session player and then saying, ‘do something around this’. And then we record it and then we take the bits we like.

Paul: So it becomes curatorial. So is that how ‘Return To Return’ came to be on the new album? That melody?

Andy: Yes quite a lot of that is generative but it's like just a very simple output of stuff that we then site and edit. We've been doing that kind of generative work for a long time now, because it's pretty straightforward to do it that way in comparison to moving notes around a score or scale on a screen.

Paul: What were you listening to when the album was coming together? Were you listening to Italo Disco and that sound in places?

Ed: I think unashamedly a few of the tracks are backward looking to the 80s and 70s on this one. It’s our attempt to try and capture that spirit as we're hitting our 30th year. This album is a bit of a statement to say, ‘this is this is us and this is what we do’. So we've kind of pulled from different parts of our career and influences and hopefully it's a nice mix.

Paul: You can hear the ones that reference the sort of earlier days and then one's from a different time. And then like 'Return To Return’ felt like ‘Ralome’, but sort of sped up and turned inside out.

Andy: People say we have a kind of sound but I believe our output is really quite varied. I mean this album is from some kind of 70s funk weirdness but hopefully it all sits together somehow with the production.

//

On that note our interview concludes. There was more talk of drug dealers taking drum machines and a rug over debts that were nothing to do with Plaid, a heavy delve into maths and physics and a chat about an anime soundtrack Plaid completed a few years back.

Plaid's new album 'Feorm Falorx' is out on the 11th November on Warp Records. Thanks to Ed & Andy and Matthew of ALM Busy Circuits.